One by one, the Union soldiers crawled out of the fetid tunnel into Richmond’s dark streets.

A rush of fetid air and a chorus of “Fresh fish! Fresh fish!” greeted Colonel Thomas Rose of the 77th Pennsylvania Volunteers when the thick wooden door to the second floor of the old Richmond tobacco warehouse was pulled open. As his eyes adjusted to the darkness, he was besieged by a mass of smelly humanity: haggard men wrapped in fragments of blankets, demanding news of the outside world. “Tell us what happened at Chickamauga.” Or “What news from the Army of the Potomac?” Weary from a long journey, Rose answered as best he could. Ten days earlier he had faced a sudden mass attack by the Confederates at Chickamauga. Grabbing the regimental colors and charging into the melee, Rose had tried heroically to rally his troops, but the overwhelming gray force crushed them. The flag was captured, along with hundreds of his men. There was little else to tell his fellow prisoners, who soon shrank back into the shadows, leaving the newcomer to find a space he could call his own in the teeming, squalid jail.

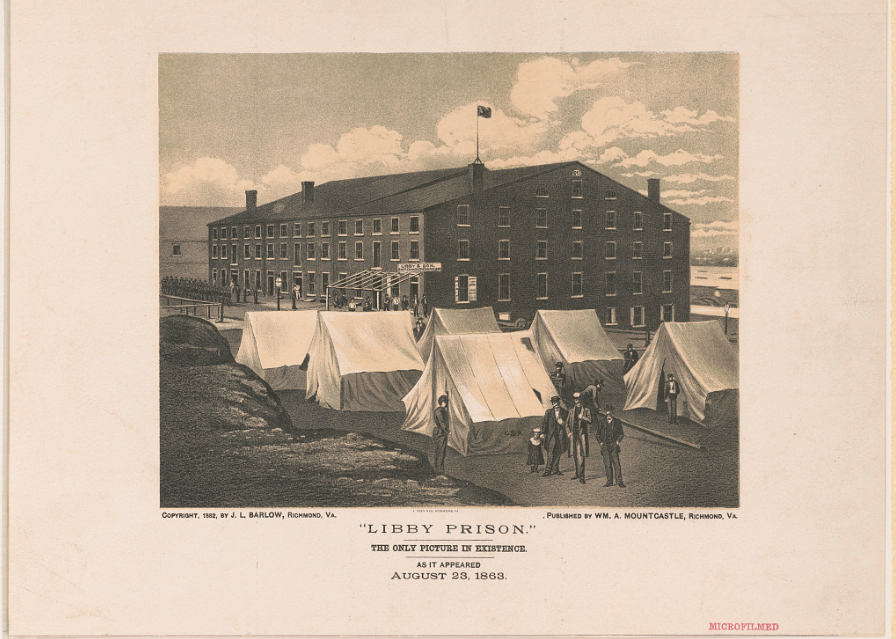

By the fall of 1863 Libby Prison, called by some the “Bastille of the Confederacy,” was a household word in the North, as notorious as Guantanamo or Abu Ghraib are today. Everyone had heard accounts of the wanton brutality, starvation and deprivation that were commonplace at the converted Richmond tobacco warehouse.

Escapes from Libby were rare, usually involving single prisoners posing as Confederates who just walked out the front door. Most were recaptured before they reached Union lines, 45 miles southeast of the Rebel capital. An organized mass escape had never been attempted before Rose arrived, but that didn’t deter the colonel. The loss of his regimental colors at Chickamauga had humiliated him beyond words. He vowed to escape, to return to his regiment and to fight with a vengeance until the Southern rebellion was smothered. Within hours of arriving, Tom Rose had begun to plot a way out of Libby Prison.

Four months later he succeeded in engineering the largest prison breakout in modern history. Of 109 Union officers who managed to crawl through his tunnel that fateful night in February 1864, 59 would make it to the safety of Yankee lines. Colonel Rose, however, was not among them.

Within days, accounts of the escape began to appear in Northern newspapers. Before the end of that year books about the daring breakout began to hit the shelves. All purported to tell the “complete story,” but most failed to mention Rose’s singular role in the plan.

Tom Rose was finally exchanged in late April 1864, and by June had returned to his regiment, which was then with William T. Sherman in Chattanooga. He fought with distinction during the remainder of the war, honored with a brevet brigadier generalship for his performance in battle.

But his daring escape clearly remained in his thoughts even after the war ended. In an 1866 letter to Pittsburgh lawyer and Civil War General Jacob B. Sweitzer, seeking an endorsement for an appointment to the Regular Army, Rose commented with some bitterness, “I have never received sufficient reward for that famous adventure for I contend that I am entitled to the entire credit of that affair.” He won his appointment, but the recognition he sought continued to elude him.

In 1888 Libby Prison was purchased by a Chicago syndicate. The plan was to dismantle the old tobacco warehouse, move it to Chicago, re-erect it behind a crenellated wall (opposite the site of the World’s Columbian Exposition, due to open in 1893), and turn it into a war museum.

When the prison museum opened in September 1889, former inmates were eager to share their accounts of captivity, generating a fresh round of published reminiscences and even a Broadway play, A Fair Rebel, which premiered in New York City in August 1891 (a film version was created in 1914, starring Dorothy Gish and directed by Frank Powell). This served to renew national interest in the prison as well as the great escape. The “Libby Prison Museum Association,” the for-profit managers of the complex, published many accounts, most of which credited Rose with engineering the breakout. One of the best was by his tunneling partner, Andrew G. Hamilton.

All in all, it was a propitious time for Rose to make his rightful claim as the “projector of the celebrated tunnel.” He was persuaded by the former state historian of Pennsylvania, Samuel P. Bates, to set the record straight by publishing his own account in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. What follows is based on Rose’s narrative of his capture, imprisonment and escape.

Colonel Rose got to Libby the day after the other Chickamauga prisoners, arriving in Richmond in a passenger car rather than crammed into a filthy boxcar. The delay occurred because he had managed to escape from the POW train when it halted at Weldon, N.C., and spent a day wandering in the woods before being recaptured. He blamed an injured foot on his inability to evade the Rebels: “I was still very lame from the effects of a broken foot from Murfreesboro, Tennessee,” where his regiment had over-wintered.

Even as Rose was settling into Libby life, he began making note of the daily routine followed by prison guards and officers—there were just 25 in total. “I thought that the whole party could be captured without alarm,” he wrote, “and for this purpose organized a society among the prisoners called the Council of Five.” The plan, admittedly grandiose, was to overpower the guards, release men from other Richmond prisons (a total of nearly 16,000 Union officers and men were then being held in the city), arm them by storming the arsenals, capture President Jefferson Davis if possible, and march south to the Federal lines near Williamsburg. The council grew like topsy, reaching 420 men—a third of the prison’s population—within a couple of weeks. Keeping it secret proved impossible. The Confederates got wind of the operation and immediately tightened security, quashing his plan.

Undaunted, Rose carried on independently. But while he was exploring the prison’s basement he stumbled upon Captain Andrew Hamilton of the 12th Kentucky Cavalry, who was also seeking a way out. Together they next turned their attention to Libby’s carpenter’s shop. “The plan was to stand by the door on the inside of the shop, and when the sentinel had just passed, to slip out while his back was in that direction and walk off,” Rose said. He tried it, only to have the guard at the other end of the building spot him and call out. Running back into the shop, “which was as dark as Erebus,” Rose then climbed a rope up to the first floor and safety. A few days later he tried again, but this time he was discovered by one of the workmen. “I seized a broad-axe with the intention of braining him if he attempted to call the guard, but he begged me not to come in there again.”

“My next plan was to escape from the room under the hospital,” Rose remembered. To do so, he and Hamilton had to cut a vertical passageway in the wall between the cooking-room, where the prisoners prepared and ate their meals, and the hospital. They soon discovered the perfect site, a fireplace behind one of the stoves. Using tools stolen from the carpenter’s shop, they began removing bricks. Rose recalled, “We were obliged to make no noise; for one of the sentinels was just outside within ten feet of where we were.”

Over the course of several nights, the pair completed a small opening in the wall. Was it large enough for a man to squeeze through? Rose decided to find out. “As soon as my feet and legs were dangling below, the inevitable law of gravitation forced my body into the hole as tight as a wedge. I was perfectly helpless.” Hamilton, try as he might, was unable to budge him. “I feared that the whole Southern Confederacy could not loosen me,” Rose recalled. The captain ran upstairs to rouse a friend, and the two men managed to extricate him with one strenuous wrench. “We all three fell upon the floor with a prodigious noise,” wrote Rose. “The sentinel seemed startled and confused.” The ruckus even woke up the prisoners on the floor above, and the noisemakers held their breath for what seemed an eternity, expecting their jailers to burst through the door any second, bayonets at the ready. To their great relief, no one came. To prevent a repeat, Rose made the hole larger.

Once they had access to the basement room below the prison hospital, Rose decided to dig under the foundation to reach a sewer that led to the James River canal behind Libby. He organized a working party of 14 men whom he swore to absolute secrecy. Each night some of the diggers lowered themselves through the hole in the cooking-room to go to work. “The indescribably bad odor and impure atmosphere of the cellar made some of them sick,” wrote Rose. “The uncomfortable positions in which they had to work amid crawling rats—the cellar was called Rat Hell—was unendurable to some.” Nevertheless, they cut out part of the foundation’s stonework, only to find that the building rested on wooden piles. “To cut through these was a tremendous undertaking; but we toiled at it night after night until we got through.” Once they started tunneling through the soil, however, they were inundated by streams of water, putting a halt to that endeavor. The prospect of escape now seemed so dim that all the diggers except Rose and Hamilton gave up.

“We two then tried another plan,” Rose recalled: to dig through the prison waste sewer. The work went well, though it was ferociously odorous, until part of the sewer caved in outside. The Pennsylvanian wrote, “We heard the rattling of the bricks and the call of the sentinel for the corporal of the guard.” Lucky for the Yankees, the prison officers thought the collapse was due to the many rats that called Libby home. But it put a halt to that tunnel.

These fruitless endeavors had consumed two months, and Hamilton was by that time on the verge of giving up, but Rose still had mettle aplenty: “I did not despair, but resolved to organize another party and dig straight through from the northeast corner to a yard enclosed by a high board fence directly across the street.” The group of diggers he formed this time included men from the earlier effort. “None of them seemed to have much hope,” Rose later wrote, “but several said they would work for no other purpose than to ‘pass away the time.’” And thus, on January 23, 1864, Thomas Rose and his crew set to work cutting a hole directly through the foundation. The two men assigned to getting through the stone wall, Major Bedan McDonald of the 101st Ohio and Captain Terrence Clarke of the 79th Illinois, managed to accomplish their task in one day.

Now came the actual digging. The soil was compacted sand, “nearly as hard as a rock,” Rose said. “We made very rapid progress until we had proceeded about fifteen feet, when the air became so vitiated as to support life but a very short time.” To provide fresh air, they used a wooden panel as a fan, worked by one of the men just outside the tunnel. To remove the dirt they used a wooden spittoon tied to a loop of clothes line, then spread the soil evenly around the floor of Rat Hell. Things went speedily until “an event occurred which effectually put a stop to our work in the daytime,” as Rose recorded, “and greatly embarrassed all our operations” That event was a special roll call conducted by the commandant of the prison, Major Thomas Turner. Normally the prisoners were counted daily, standing “in four ranks; then Ross, the clerk, would pass down the front rank and count the files. As long as they pursued this method we had no difficulty in accounting for absentees” who might be working on the tunnel. As soon as a man had been counted by the clerk, “all he had to do was stoop and run quickly to the left of the line before Ross got there, and be counted a second time. Other prisoners used to see us dodging around and thought we were doing it for fun—devilment they called it; and they got to doing the same thing—for devilment sure enough.” This threw Ross’ totals off for a number of days running, catching Turner’s attention. That’s when he called the special roll call.

All the inmates were placed in one room and counted as they passed through the door. There was no chance for devilment this time. During the roll call two of Rose’s men were digging in the cellar, Captain Isaac N. Johnston of the 6th Kentucky Infantry, and Major McDonald. Came the call: “I.N. Johnston.” No response. “I.N. Johnston.” Still no response. Twice more, “I.N. Johnston.” A notation was made on the rolls, and the count continued until McDonald’s name was called. Rose wrote, “This affair caused me considerable concern, as it awakened not only a great curiosity among the prison officials, but also among the prisoners themselves.” What to do? “There were only two plans for them to pursue. One was to face the music. The other was to remain concealed every day down below.” McDonald chose to come up; Johnston opted to stay in Rat Hell. Fortunately the disappearance of the Kentucky captain seemed to raise no alarms among the prison’s staff. Work on the tunnel shifted back to nights.

A more startling event followed some days later. McDonald, who was serving as the digger, “got it into his head that we had reached the desired point across the alley.” Rose wrote, “I tried to convince him of the absurdity of the notion.” He calculated that they still had 10 feet to go before they were safely under the fenced enclosure, but “McDonald insisted on striking at once towards the surface. I told him that I wanted it distinctly understood that they were not far enough; but he might go cautiously to the surface to let fresh air into the tunnel, and to satisfy himself” that the tunnel was not yet long enough. “I then went up-stairs and retired.” A confident McDonald dug toward the surface. When he suddenly broke through, he nearly panicked when he heard the guards, who seemed to be right on top of him. The young officer raced back upstairs to tell Rose. “McDonald came to me in great consternation, and told me the whole thing was discovered,” Rose wrote. “He said he had come right to the feet of the sentinel. We went below, and I noticed that the tread of the sentinel did sound very loud. The orifice at the surface was little larger than a rat-hole. I took one of my working garments and shoved it into the hole.” McDonald’s breach was never discovered

At that point Rose decided that he and Hamilton alone would finish the tunnel. Over two nights, the pair dug all the way through to the yard. Rose recalled: “On the night of the 9th of February, 1864, my party assembled as soon as it began to get dark. I started out, immediately followed by Hamilton. We then went together down to the gate, and as soon as the sentinel’s back was turned, slipped out, walked down the street along the canal to the first corner, then went north.” When they came to a hospital guarded by Rebel soldiers, the two separated. “I did not see him again for several months,” Rose wrote.

Now on his own, Rose headed due east along the tracks of the York River Railroad. As it happened, he was attempting to make his way across country amid one of the coldest winters in memory. A slow, cold march of 11 miles brought him to the Chickahominy River, where he turned south, soon stumbling upon a camp of Rebel cavalry. “It was just daylight, and they were sounding reveille,” he recalled. “I found a large sycamore tree that was hollow. I concealed myself in this until the late afternoon.” First making sure there was no one around, Rose then waded across the Chickahominy. “It was pretty deep, and I got my clothes thoroughly soaked.”

Heading southeast, he came across another group of enemy cavalry. Rose lay upon the ground, waiting until dark to move on. But “When I attempted to rise,” he wrote, “I found myself perfectly stiff and my clothes completely frozen. I was in great danger of freezing to death.” The next night Rose risked making a fire to warm himself. “I was soon in a profound sleep. When I awoke, I found that I had been nearly in as much danger of burning to death as I was of freezing. My coat was burned through in several places, as well as my pants.” He pressed on, reaching New Kent Courthouse that evening.

Rose would have been astonished to learn that a total of 108 of his fellow inmates had crawled through his tunnel on the night of the 9th. Nor did he know—though he must have suspected from all the Rebel activity he saw around him—that the Confederates had thrown a huge dragnet around Richmond and down the Peninsula in an effort to recapture the fleeing Yankees. In response, the Union sent out the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry to pick up any escapees they could find. But all Tom Rose knew at that point was that he was cold and hungry and only halfway to reaching safety.

Just outside New Kent he had his first face-to-face encounter with a Rebel picket. “The man rode up to me,” Rose wrote. “He was a stupid fellow, and asked me if I belonged to the New Kent cavalry. I had on a gray cap. Of course I answered in the affirmative. He turned and rode back.” Rose jumped into a nearby thicket of laurel “as fast as my lame foot would permit.” But now he had been spotted, and a group of cavalry was soon in full pursuit. Coming out the other side of the woods, the Yankee found himself facing a half-mile of open field, with a small gully running across it. “This was neither wide nor deep, but it afforded my only chance of escape. I threw myself into it and crawled the entire distance without raising my head. When I reached the end of the gully I found myself at the Williamsburg road.” Limping into a patch of pines, Rose hid for several hours before cautiously moving on.

He spent much of the following day darting in and out of the woods that lined the road to freedom. Sometime that morning Rose “came to an open space. Here, to my joy, I saw a body of United States troops moving on the road to my left. I sat down and awaited their approach.” The colonel remained wary. Hearing a noise behind him, he turned to see a trio of Union pickets. Their sudden appearance “excited a suspicion that all was not right.” After a few minutes the sentinels began to walk toward the mass of troops further down the road. Rose took this to be a good sign, following them from a distance.

When they spotted the bedraggled man, they called him over. “As soon as I came close to them, I saw that I was entrapped. I endeavored to make them believe I was a rebel soldier.” For he now realized these men were not Yankees, but Confederates dressed in Federal uniforms. “My first impulse was to break and run, but my lameness and enfeebled condition prevented me from doing this.” Rose was once again in the hands of his enemy. One of the Rebels began to lead him off across the field. “I started off with him, limping fearfully.” When they were halfway across, Rose “sprang suddenly upon him, disarmed and prostrated him, fired off his piece and started to run towards the troops, and would easily have escaped had it not been for my lameness.” Soon Confederates were popping up from hiding places to pursue the prisoner. Two ran him down, beating him with their muskets, then carried him to a ravine a few hundred yards distant— away from the Union troops marching over the next rise.

“The man I had disarmed seemed to be badly hurt,” Rose wrote. “He wanted to kill me at once.” An officer intervened, though he instructed the guards to “by no means let me escape or be taken from them alive.” A local farmer was enlisted to guide the Rebels around the Yankee troops, who were, the man told them, “thick as hornets on the other road.”

Rose was returned to Libby Prison that frigid February and thrown into the dungeon for 10 days. Released from the cell at the beginning of March, he returned to his quarters upstairs. He had entered the prison five months earlier determined to escape, and the evidence suggests he thought of nothing else during his incarceration. That he made no further efforts after his recapture may have had to do with a series of special exchanges that began early that spring. “This took out most of the officers of higher rank,” he recalled, “and soon I was the only colonel left in the prison.” But finally, on April 30, 1864, Rose himself was exchanged. After a short stay at a military hospital in Annapolis, Md., he returned home to Pittsburgh and was reunited with his wife and children. He rejoined the 77th Pennsylvania, as its colonel, in early June.

Today the only reminder in Richmond that the “Bastille of the Confederacy” ever existed is a simple plaque mounted to the city’s flood wall along the James Canal. It reads: “On this site stood Libby Prison, C.S.A., 1861- 1865, Federal Prisoners of War.”

###

Steven Trent Smith is an Emmy-award-winning photojournalist whose video assignments have taken him to battle sites such as Gettysburg, Brandywine, Little Big Horn and Flanders. He is also the author of two non – fiction books on submarines, The Rescue and Wolf Pack. For additional reading, he recommends Joseph Wheel – an’s Libby Prison Breakout and James Gindel sperger’s Escape From Libby Prison.

Originally published in the August 2010 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.