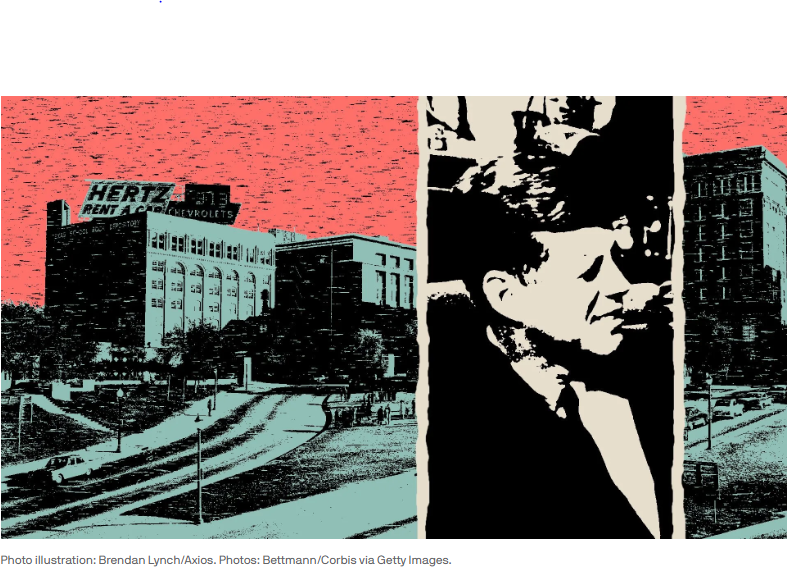

On Nov. 22, 1963, a series of shots rang out in Dealey Plaza just as President John F. Kennedy’s open limousine passed through.

- The president was fatally wounded — and Dallas would never be the same.

Why it matters: Those five seconds changed the arc of global history. They also permanently reshaped North Texas in ways that are still reverberating 60 years later.

What’s happening: Several events around North Texas are commemorating the 60th anniversary of the assassination, and the subsequent hunt for the president’s killer.

- The Texas Theatre, where Lee Harvey Oswald was taken into custody, will be screening “War Is Hell,” the film Oswald snuck into after shooting Dallas officer J.D. Tippit while Tippit questioned him at the corner of 10th Street and Patton Avenue in Oak Cliff.

- The theater’s lobby will be open to the public on Wednesday, displaying a photo exhibit curated by John Slate from The Dallas Municipal Archives, detailing Oswald’s presence in Oak Cliff.

- A new exhibit at UNT Law School, which occupies the former Dallas police station where Oswald was gunned down by nightclub owner Jack Ruby, details what happened to Oswald after his arrest.

- The Sixth Floor Museum, housed in the former Texas School Book Depository where Oswald perched, chronicles Kennedy’s 1963 trip through Texas and the historical context of the assassination.

Flashback: Dallas in 1963 was a city “on the verge of a nervous breakdown,” Pulitzer Prize-winning author Lawrence Wright, who was in algebra class at Woodrow Wilson High School when the president was killed, recently told the Dallas Morning News.

- Dallas was segregated and controlled at the time by a powerful group of right-wing business and religious leaders.

Context: Dallas was home to Edwin Walker, a former Army general known nationally for his staunch conservative and anti-communist opinions. He viewed Kennedy as a Marxist threat.

- A few months before Kennedy’s assassination, Oswald attempted to kill Walker at his home on Turtle Creek Boulevard with the same Italian rifle used the day Kennedy was shot.

- The Rev. W.A. Criswell, longtime senior pastor at First Baptist Dallas, was an outspoken anti-Catholic critic of Kennedy’s. Before the 1960 election, Dallas business leaders paid for 200,000 copies of an anti-Kennedy sermon by Criswell to be distributed around the country.

- Less than a month before the assassination, U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson was attacked with signs in Dallas by right-wing hecklers organized by Walker. The incident prompted Stanley Marcus, then-president of Neiman Marcus, to prophetically warn the White House that Kennedy should skip Dallas on his visit to Texas.

- In the days before Kennedy’s arrival, “Wanted for Treason” posters bearing a mug-shot-style photo of the president began circulating on Dallas streets.

The big picture: After the assassination, Dallas was known nationally as the “city of hate.”

The economic impact

After the assassination, news coverage blamed the political climate in Dallas for the president’s murder. Companies and individuals across the country refused to do business in North Texas.

- So the Dallas Citizens Council, the collection of oligarchs who ran Dallas at the time, quickly developed a plan to rehabilitate the city’s image.

State of play: The Citizens Council wanted J. Erik Jonsson, the 63-year-old co-founder and chairman of Texas Instruments, to replace Earle Cabell as mayor. At the time, Texas Instruments was one of the leading tech companies in the world, known for developing transistors, semiconductors and integrated circuits.

- In February 1964, Jonsson was elected mayor. Before taking office, he hired urban designer Vincent Ponte to accompany him on a tour of the world’s greatest cities to find inspiration for ways to improve Dallas.

What they did: As the story goes, Jonsson was standing on a hotel balcony in Athens overlooking the port of Piraeus when he realized that all of the places he visited had one thing in common — they were all port cities.

Yes, but: The Trinity River flows through Dallas, but it’s mostly unnavigable, making North Texas one of the most populous landlocked regions in the world.

- So if Dallas were to become a port, the thinking went, it would need to become a hub of air traffic — something the single-terminal Love Field Airport couldn’t sustain.

What happened: Jonsson worked with the Federal Aviation Administration and regional business leaders to build a new airport. In 1974, DFW International Airport opened midway between Dallas and Fort Worth.

- Today it’s one of the busiest airports in the world.

Quick take: The airport led to an influx of corporate business. Today, two of the top 30 global Fortune 500 companies — McKesson and AT&T — are headquartered in North Texas and the region has become a fulcrum for American business.

- The area is also home to two of the nation’s largest air carriers: American Airlines and Southwest Airlines.

- That’s led to the region’s massive population growth over the last few decades.

By the numbers: In 1963, the population of Dallas-Fort Worth was 1.6 million. At the beginning of that decade, it was the 12th most populous metro area in the country.

- Today, more than 8 million people live in North Texas, making it the nation’s fourth largest metro area.

The cultural impact

The city of Dallas has transitioned from a hotbed of right-wing extremism to a Democratic stronghold. It’s also changed from a place that was 75% white to majority non-white.

- But around the world, Dallas is still best known as the city of JFK’s assassination.

Between the lines: Generations who lived through that era have talked about the collective guilt felt by North Texans, which city leaders are still reckoning with.

- For decades, it was an unspoken trauma for many people. Newcomers learned that it was a taboo subject of conversation.

Details: Many people in the Black community believed Kennedy was killed because of his position on civil rights issues, former state legislator Helen Giddings said during a recent panel discussion hosted by the UNT Law School.

What they’re saying: “Can we do more with our hearts and somehow find a way to get all of us to be willing to create and embrace a culture of civility and inclusiveness?” Giddings asked at the event.

Lingering reminders

Reminders of what happened in Dealey Plaza in 1963 are found all over the region.

Zoom in: At least two bars — Lee Harvey’s in the Cedars and Kennedy Room in Uptown — have names that invoke the assassination.

- Less than a mile from the crowded bars and restaurants in Bishop Arts, a state historical marker notes the spot where Tippit was killed.

- A plaque at Parkland Memorial Hospital reminds visitors where doctors operated on Kennedy in what was then Trauma Room One.

- Another plaque at Dallas Love Field commemorates Vice President Lyndon Johnson’s presidential oath of office, just hours after Kennedy’s death, while Air Force One was parked at the airport.

- A rooming house in Oak Cliff where Oswald stayed has become a makeshift museum.

Meanwhile: There’s a near-constant stream of new books, movies and podcasts hoping to solve the mysteries surrounding the assassination.

Plus: Dealey Plaza is still a beacon for conspiracy theorists, including the faction of QAnon believers who flocked there two years ago hoping to witness the return of John F. Kennedy Jr., who died in a plane crash in 1999.

The bottom line: That brief moment in 1963 will continue to define and shape Dallas’ legacy, for better and worse.