After George Floyd was killed, Donald Trump sensed an opportunity. Americans, anguished and angry over Floyd’s death, had erupted in protest—some set fires, broke the windows of department stores, and stormed a police precinct. Commentators reached for historical analogies, circling in on 1968 and the twilight of the civil-rights era, when riots and rebellion engulfed one American city after another. Back then, Richard Nixon seized on a message of “law and order.” He would restore normalcy by suppressing protest with the iron hand of the state. In return for his promise of pacification, Americans gave him the White House.

Surveying the protests, Trump saw a path to victory in Nixon’s footsteps: The uprisings of 2020 could rescue him from his catastrophic mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic. The president leaned into his own “law and order” message. He lashed out against “thugs” and “terrorists,” warning that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Ahead of what was to be his comeback rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in June, Trump tweeted, “Any protesters, anarchists, agitators, looters or lowlifes who are going to Oklahoma please understand, you will not be treated like you have been in New York, Seattle, or Minneapolis”—making no distinction between those protesting peacefully and those who might engage in violence.

In this, Trump was returning to a familiar playbook. He was relying on the chaos of the protests to produce the kind of racist backlash that he had ridden to the presidency in 2016. Trump had blamed the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri—a response to the shooting of Michael Brown by a police officer—on Barack Obama’s indulgence of criminality. “With our weak leadership in Washington, you can expect Ferguson type riots and looting in other places,” Trump predicted in 2014. As president, he saw such uprisings as deliverance.

Then something happened that Trump did not foresee. It didn’t work.

Trump was elected president on a promise to restore an idealized past in which America’s traditional aristocracy of race was unquestioned. But rather than restore that aristocracy, four years of catastrophe have—at least for the moment—discredited it. Instead of ushering in a golden age of prosperity and a return to the cultural conservatism of the 1950s, Trump’s presidency has radicalized millions of white Americans who were previously inclined to dismiss systemic racism as a myth, the racial wealth gap as a product of Black cultural pathology, and discriminatory policing as a matter of a few bad apples.

Those staples of the American racial discourse became hard to sustain this year, as the country was enveloped by overlapping national crises. The pandemic exposed the president. The nation needed an experienced policy maker; instead it saw a professional hustler, playing to the cameras and claiming that the virus would disappear. As statistics emerged showing that Americans of color disproportionately filled the ranks of essential workers, the unemployed, and the dead, the White House and its allies in the conservative media downplayed the danger of the virus, urging Americans to return to work and resurrect the Trump economy, no matter the cost.

Meanwhile, the state’s seeming indifference to an epidemic of racist killings continued unabated: On February 23, Ahmaud Arbery was fatally shot after being pursued by three men in Georgia who thought he looked suspicious; for months, the men walked free. On March 13, Breonna Taylor, an emergency-room technician, was killed by Louisville, Kentucky, police officers serving a no-knock warrant to find a cache of drugs that did not exist; months later, one of the officers was fired but no charges were filed. Then, on Memorial Day, the Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on Floyd’s neck and ignored his many pleas for help. The nation erupted. According to some polls, more than 23 million people participated in anti-police-brutality protests, potentially making this the largest protest movement in American history.

American history has produced a few similar awakenings. In 1955, the images of a mutilated Emmett Till helped spark the civil-rights movement. In 2013, the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer inspired Alicia Garza to declare that Black lives matter, giving form to a movement dedicated to finishing the work begun by its predecessors. Just as today, the stories and images of shattered Black lives inspired Americans to make the promises of the Declaration of Independence more than just a fable of the founding. But almost as quickly, the dream of remaking society faltered, when white Americans realized what they would have to sacrifice to deliver freedom. The urgent question now is whether this time is different.

The conditions in America today do not much resemble those of 1968. In fact, the best analogue to the current moment is the first and most consequential such awakening—in 1868. The story of that awakening offers a guide, and a warning. In the 1860s, the rise of a racist demagogue to the presidency, the valor of Black soldiers and workers, and the stories of outrages against the emancipated in the South stunned white northerners into writing the equality of man into the Constitution. The triumphs and failures of this anti-racist coalition led America to the present moment. It is now up to their successors to fulfill the promises of democracy, to make a more perfect union, to complete the work of Reconstruction.

They came for George Ruby in the middle of the night, as many as 50 of them, their faces blackened to conceal their identities. As the Confederate veterans dragged Ruby from his home, they mocked him for having believed that he would be safe in Jackson, Louisiana: “S’pose you thought the United States government would protect you, did you?” They dragged him at least a mile, to a creek, where they beat him with a paddle and left him, half-dressed and bleeding, with a warning: Leave, and never return.

One of the few Black agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the federal agency established to facilitate the transition of the emancipated from slavery to freedom in the South, Ruby had come to Jackson in 1866 to open a school for the newly liberated. Although some of the men who attacked Ruby were eventually tried, under the guard of Black Union soldiers, Ruby heeded his attackers’ warning. But his choice of destination—Texas—would make him a frequent witness to the same violence he fled.

“Texas was very violent during the early years of Reconstruction,” Merline Pitre, a historian and biographer of Ruby, told me. One observer at the time said that “there was so much violence in Texas that if he had to choose between hell and Texas, he would have chosen hell.”

Ruby traveled through the state reviewing the work of the Freedmen’s Bureau and sending dispatches to his superiors. As the historian Barry A. Crouch recounts in The Dance of Freedom, Ruby warned that the formerly enslaved were beset by the “fiendish lawlessness of the whites who murder and outrage the free people with the same indifference as displayed in the killing of snakes or other venomous reptiles,” and that “terrorism engendered by the brutal and murderous acts of the inhabitants, mostly rebels,” was preventing the freedmen from so much as building schools.

The post–Civil War years were a moment of great peril for the emancipated, but also great promise. A stubborn coterie of Republican Radicals—longtime abolitionists and their allies—were not content to have simply saved the Union. They wanted to transform it: to make a nation where “all men are created equal” did not just mean white men.

But the country was exhausted by the ravages of war. The last thing most white Americans wanted was to be dragged through a bitter conflict over expanding the boundaries of American citizenship. They wanted to rebuild the country and get back to business. John Wilkes Booth had been moved to assassinate Abraham Lincoln not by the Confederate collapse, but by the president’s openness to extending the franchise to educated Black men and those who had fought for the Union, an affront Booth described as “nigger citizenship.”

Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, viewed the Radical Republican project as an insult to the white men to whom the United States truly belonged. A Tennessee Democrat and self-styled champion of the white working class, the president believed that “Negroes have shown less capacity for government than any other race of people,” and that allowing the formerly enslaved to vote would eventually lead to “such a tyranny as this continent has never yet witnessed.” Encouraged by Johnson’s words and actions, southern elites worked to reduce the emancipated to conditions that resembled slavery in all but name.

Throughout the South, when freedmen signed contracts with their former masters, those contracts were broken; if they tried to seek work elsewhere, they were hunted down; if they reported their concerns to local authorities, they were told that the testimony of Black people held no weight in court. When they tried to purchase land, they were denied; when they tried to borrow capital to establish businesses, they were rejected; when they demanded decent wages, they were met with violence.

In the midst of these terrors and denials, the emancipated organized as laborers, protesters, and voters, forming the Union Leagues and other Republican clubs that would become the basis of their political power. Southern whites insisted that the freedmen were unfit for the ballot, even as they witnessed their sophistication in protest and organization. In fact, what the former slave masters feared was not that Black people were incapable of self-government, but the world the emancipated might create.

From 1868 to 1871, Black people in the South faced a “wave of counter-revolutionary terror,” the historian Eric Foner has written, one that “lacks a counterpart either in the American experience or in that of the other Western Hemisphere societies that abolished slavery in the nineteenth century.” Texas courts, according to Foner, “indicted some 500 white men for the murder of blacks in 1865 and 1866, but not one was convicted.” He cites one northern observer who commented, “Murder is considered one of their inalienable state rights.”

The system that emerged across the South was so racist and authoritarian that one Freedmen’s Bureau agent wrote that the emancipated “would be just as well off with no law at all or no Government.” Indeed, the police were often at the forefront of the violence. In 1866, in New Orleans, police joined an attack on Republicans organizing to amend the state constitution; dozens of the mostly Black delegates were killed. General Philip Sheridan wrote in a letter to Ulysses S. Grant that the incident “was an absolute massacre by the police … perpetrated without the shadow of a necessity.” The same year, in Memphis, white police officers started a fight with several Black Union veterans, then used the conflict as a justification to begin firing at Black people—civilians and soldiers alike—all over the city. The killing went on for days.

These stories began to reach the North in bureaucratic dispatches like Ruby’s, in newspaper accounts, and in testimony to the congressional committee on Reconstruction. Northerners heard about Lucy Grimes of Texas, whose former owner demanded that she beat her own son, then had Grimes beaten to death when she refused. Her killers went unpunished because the court would not hear “negro testimony.” Northerners also heard about Madison Newby, a former Union scout from Virginia driven by “rebel people” from land he had purchased, who testified that former slave masters were “taking the colored people and tying them up by the thumbs if they do not agree to work for six dollars a month.” And they heard about Glasgow William, a Union veteran in Kentucky who was lynched in front of his wife by the Ku Klux Klan for declaring his intent to vote for “his old commander.” (Newspapers sympathetic to the white South dismissed such stories; one called the KKK the “phantom of diseased imaginations.”)

The South’s intransigence in defeat, and its campaign of terror against the emancipated, was so heinous that even those inclined toward moderation began to reconsider. Carl Schurz, a German immigrant and Union general, was dispatched by the Johnson administration to investigate conditions in the South. Schurz sympathized with white southerners who struggled to adjust to the new order. “It should not have surprised any fair-minded person that many Southern people should, for a time, have clung to the accustomed idea that the landowner must also own the black man tilling his land, and that any assertion of freedom of action on the part of that black man was insubordination equivalent to criminal revolt, and any dissent by the black man from the employer’s opinion or taste, intolerable insolence,” he wrote.

The horrors he witnessed, however, convinced him that the federal government had to intervene: “I saw in various hospitals negroes, women as well as men, whose ears had been cut off or whose bodies were slashed with knives or bruised with whips, or bludgeons, or punctured with shot wounds. Dead negroes were found in considerable number in the country roads or on the fields, shot to death, or strung upon the limbs of trees. In many districts the colored people were in a panic of fright, and the whites in a state of almost insane irritation against them.”

When Schurz returned to Washington, Johnson refused to hear his findings. The president had already set his mind to maintaining the United States as a white man’s government. He told Schurz that a report was unnecessary, then silently waited for Schurz to leave. “President Johnson evidently wished to suppress my testimony as to the condition of things in the South,” Schurz wrote in his memoir. “I resolved not to let him do so.”

The stories of southern violence radicalized the white North. “The impression made by these things upon the minds of the Northern people can easily be imagined,” Schurz wrote. “This popular temper could not fail to exercise influence upon Congress and stimulate radical tendencies among its members.”

Still convinced that most of the country was on his side, Johnson sank into paranoia, grandeur, and self-pity. In his “Swing Around the Circle” tour, Johnson gave angry speeches before raucous crowds, comparing himself to Lincoln, calling for some Radical Republicans to be hanged as traitors, and blaming the New Orleans riot on those who had called for Black suffrage in the first place, saying, “Every drop of blood that was shed is upon their skirts and they are responsible.” He blocked the measures that Congress took up to protect the rights of the emancipated, describing them as racist against white people. He told Black leaders that he was their “Moses,” even as he denied their aspirations to full citizenship.

Johnson had reason to believe, in a country that had only just abolished slavery, that the Radicals’ attempt to create a multiracial democracy would be rejected by the electorate. What he did not expect was that in his incompetence, coarseness, and vanity, he would end up discrediting his own racist crusade, and press the North into pursuing a program of racial justice that it had wanted to avoid.

Black leaders were conscious that Johnson’s racism had, rather than weakening the cause of Black suffrage, reaffirmed its necessity. The Christian Recorder, edited by the Reverend James Lynch, editorialized that “paradoxical as it may seem, President Johnson’s opposition to our political interests will finally result in securing them to us.” The Republicans swept the 1866 midterms, and Johnson was impeached in 1868—officially for violating the Tenure of Office Act, but this was mere pretext. The real reason was his obstruction of Congress’s efforts to protect the emancipated. Johnson was acquitted, but his presidency never recovered.

The turmoil in the South, and Johnson’s enabling of it, set Congress on the path to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, ratified in 1868 and 1870, respectively. The amendments made everyone born or naturalized in the United States a citizen and made it unconstitutional to deprive Americans of the right to vote on the basis of race. Today, the principles underlying the Reconstruction amendments are largely taken for granted; few in the political mainstream openly oppose them, even as they might seek to undermine them. But these amendments are the foundation of true democracy in America, the north star for every American liberation movement that has followed.

Congress also passed laws barring racial discrimination in public accommodations, which would be quickly ignored and then, almost a century later, revived by the civil-rights movement. State governments, though not without their flaws and struggles, massively expanded public education for Black and white southerners, funded public services, and built infrastructure. On the ashes of the planter oligarchy, the freedmen and their allies sought to build a new kind of democracy, one worthy of the name.

The Reconstruction agenda was not motivated by pure idealism. The Republican Party understood that without Black votes, it was not viable in the South, and that its opposition would return to Congress stronger than it was before the war if Black disenfranchisement succeeded. Still, a combination of partisan self-interest and egalitarian idealism established the conditions for multiracial democracy in the United States.

Swept up in the infinite possibilities of the moment, even the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who before the war had excoriated America for the hollowness of its ideals, dared to imagine the nation as more than a white man’s republic with Black men as honored guests. “I want a home here not only for the Negro, the mulatto, and the Latin races; but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours,” Douglass declared in 1869. “In whatever else other nations may have been great and grand, our greatness and grandeur will be found in the faithful application of the principle of perfect civil equality to the people of all races and of all creeds, and to men of no creeds.”

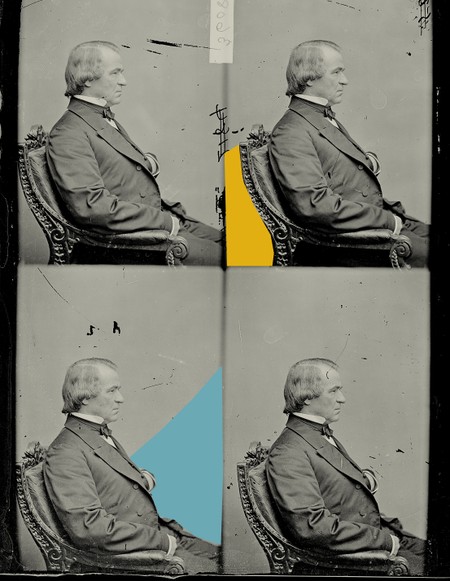

freedmen would eventually find themselves at the mercy of their former masters. (Illustration by Arsh Raziuddin; photographs by Library of Congress / Corbis / VCG / Getty; buyenlarge / Getty; Shutterstock)

Black Americans today do not face the same wave of terror they did in the 1860s. Still, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery were only the most recent names Americans learned. There was Eric Garner, who was choked to death on a New York City sidewalk during an arrest as he rasped, “I can’t breathe.” There was Walter Scott in North Charleston, South Carolina, who was shot in the back while fleeing an officer. There was Laquan McDonald in Chicago, who was shot 16 times by an officer who kept firing even as McDonald lay motionless on the ground. There was Stephon Clark, who was gunned down while using a cellphone in his grandmother’s backyard in Sacramento, California. There was Natasha McKenna, who died after being tased in a Virginia prison. There was Freddie Gray, who was seen being loaded into the back of a Baltimore police van in which his spinal cord was severed. There was Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old in Cleveland with a toy gun who was killed by police within moments of their arrival.

What these stories have in common is that they were all captured on video. Just as southern dispatches and congressional testimony about the outrages against the emancipated radicalized the white North with a recognition of how the horrors of racism shaped Black life in America, the proliferation of videos from cellphones and body cameras has provided a vivid picture of the casual and often fatal abuse of Black Americans by police.

“There’s a large swath of white people who I think thought Black people were being hyperbolic about police humiliation and harassment,” Patrisse Cullors, one of the co-founders of the Black Lives Matter movement, told me. “We started seeing more and more people share videos of white people calling the cops on Black people and using the cops as their weapon against the Black community. Those kinds of viral videos—that weren’t just about Black death, but Black people’s everyday experience with policing—have shaped a new ideology. What are the police really here for? Who are they truly protecting?”

The continual accretion of gruesome evidence of police violence has taken a toll on today’s activists; some rarely watch the videos anymore. George Floyd was killed just a few blocks from the home of Miski Noor, an organizer in Minneapolis. But Noor could watch the video of his death for only a minute before turning away.

“I’ve seen enough,” Noor told me. “I don’t want to see any more.” But the work of Cullors, Noor, and others ensured that these videos dramatically shifted public opinion about racism and American policing.

After the rise of Barack Obama, large numbers of white Americans became convinced not only that racism was a thing of the past but also that, to the extent racial prejudice remained a factor in American life, white people were its primary victims. “In 2008, in the battleground states, more white voters thought reverse discrimination was a bigger deal than classic racial discrimination,” Cornell Belcher, a pollster who worked on both of Barack Obama’s presidential campaigns, told me. The activism of Black Lives Matter, the Movement for Black Lives, and other groups, as well as the unceasing testimony of those lost to police violence, has reversed that trend. “In the past, white voters by and large didn’t think that discrimination was a real big thing. Now they understand that it is.”

A June 2020 Monmouth University poll found increases across all races in the belief that law enforcement discriminates against Black people in the U.S. The same poll found that 76 percent of Americans considered racism and discrimination a “big problem”—up from 51 percent in 2015. In a Pew Research Center poll the same month, fully 67 percent of Americans expressed some degree of support for Black Lives Matter.

These numbers are even more remarkable when considered in historical context. In 1964, in a poll taken nine months after the March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, 74 percent of Americans said such mass demonstrations were more likely to harm than to help the movement for racial equality. In 1965, after marchers in Selma, Alabama, were beaten by state troopers, less than half of Americans said they supported the marchers.

The shift that’s occurred this time around “wasn’t by happenstance,” Brittany Packnett Cunningham, an activist and a writer, told me, nor is it only the product of video evidence. “It has been the work of generations of Black activists, Black thinkers, and Black scholars that has gotten us here”—people like Angela Davis, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Michelle Alexander, and others. “Six years ago, people were not using the phrase systemic racism beyond activist circles and academic circles. And now we are in a place where it is readily on people’s lips, where folks from CEOs to grandmothers up the street are talking about it, reading about it, researching on it, listening to conversations about it.”

All of that preparation met the moment: George Floyd’s killing, the pandemic’s unmistakable toll on Black Americans, and Trump’s callous and cynical response to both.

Still, like Andrew Johnson, Trump bet his political fortunes on his assumption that the majority of white Americans shared his fears and beliefs about Black Americans. Like Johnson, Trump did not anticipate how his own behavior, and the behavior he enabled and encouraged, would discredit the cause he backed. He did not anticipate that the activists might succeed in convincing so many white Americans to see the protests as righteous and justified, that so many white Americans would understand police violence as an extension of his own cruelty, that the pandemic would open their eyes to deep-seated racial inequities.

“I think this country is at a turning point and has been for a little while. We went from celebrating the election of the first Black president in history to bemoaning a white nationalist in the White House,” Alicia Garza told me. “People are grappling with the fact that we’re not actually in a post-racial society.”

How far will the possibilities of this moment extend? We could consider two potential outcomes—one focused on police and prisons, and a broader one, aimed at eliminating the deeply entrenched systems that keep Black people from realizing full equality, a long-standing crisis Americans have tried to suppress with policing and prisons rather than attempting to resolve it.

A majority of Americans have accepted the diagnosis of Black Lives Matter activists, even if they have yet to embrace their more radical remedies, such as defunding the police. For the moment, the surge in public support for Black Lives Matter appears to be an expression of approval for the movement’s most basic demand: that the police stop killing Black people. This request is so reasonable that only those committed to white supremacy regard it as outrageous. Large majorities of Americans support reforms such as requiring the use of body cameras, banning choke holds, mandating a national police-misconduct database, and curtailing qualified immunity, which shields officers from liability for violating people’s constitutional rights.

The urgency of addressing this crisis has been underscored by the ongoing behavior of police departments, whose officers have reacted much as the white South did after Appomattox: by brutalizing the people demanding change.

In New York City, officers drove two SUVs into a crowd of protesters. In Philadelphia, cops beat demonstrators with batons. In Louisville, police shot pepper balls at reporters. In Austin, Texas, police left a protester with a fractured skull and brain damage after firing beanbag rounds unprovoked. In Buffalo, New York, an elderly protester was shoved to the ground by police in full riot gear, sustained brain damage, and had to be hospitalized. The entire riot team resigned from the unit in protest—not because of their colleagues’ behavior, but because they faced sanction for it.

Yet the more the police sought to violently repress the protesters, the more people spilled into the streets in defiance, risking a solitary death in a hospital bed in order to assert their right to exist, to not have their lives stolen by armed agents of the state. “As the uprising went on, we saw the police really responding in ways that were retaliatory and vicious,” Noor told me. “Kind of like, ‘How dare you question me and my intentions and my power?’ ”

At the height of Reconstruction, racist horrors produced the political will to embrace measures once considered impossibly idealistic, such as Black male suffrage. Many Black Lives Matter activists have a similarly radical vision. The calls to defund or abolish the police seem sudden to those who do not share their premises. But these activists see a line of continuity in American policing that stretches back to the New Orleans and Memphis killings that so outraged the postbellum white North, and back further still, to antebellum slave patrols. And although there is no firm consensus on how to put an end to this history, there is broad agreement that police should not be the solution to problems like poverty, addiction, and homelessness, and that public resources should be used to meet the needs of communities.

In the face of implacable violence across generations, simply banning choke holds and mandating body cameras are not meaningful solutions. To these activists, centuries of liberal attempts at reform have only bureaucratized the role of the police as the armed guardians of a racist system, one that fractures Black families, restricts Black people’s employment opportunities, and excludes them from the ballot box.

“I want to see the existing systems of policing and carceral punishment abolished and replaced with things that actually restore justice and keep people safe at home,” Packnett Cunningham told me.

The problem is not simply that a chance encounter with police can lead to injury or death—but that once marked by the criminal-justice system, Black people can be legally disenfranchised, denied public benefits, and discriminated against in employment, housing, and jury service. “People who have been convicted of felonies almost never truly reenter the society they inhabited prior to their conviction. Instead, they enter a separate society, a world hidden from public view, governed by a set of oppressive and discriminatory rules and laws that do not apply to everyone else,” Michelle Alexander wrote in The New Jim Crow in 2010. “Because this new system is not explicitly based on race, it is easier to defend on seemingly neutral grounds.”

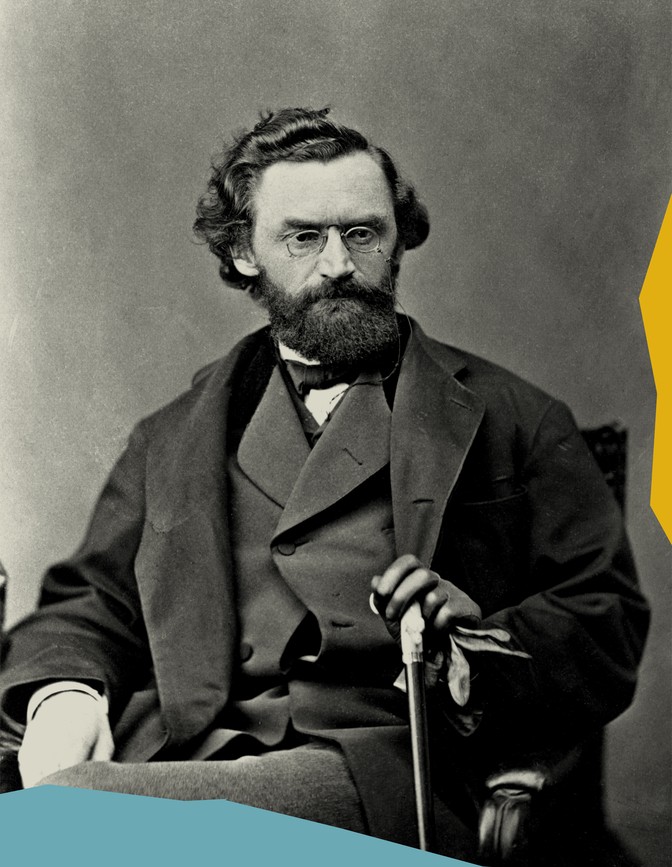

would be more promising if he were not an author of the system he now opposes. (Illustration by Arsh Raziuddin; photographs by William Thomas Cain / Getty; Mark Reinstein / Corbis / Getty; Mel D. Cole)

In the aftermath of the Ferguson protests, it was fashionable to speak of a “new civil-rights movement.” But it is perhaps more illuminating to see Black Lives Matter as a new banner raised on the same field of battle, stained by the blood of generations who came before. The fighters are new, but the conflict is the same one that Frederick Douglass and George Ruby fought, one that goes far beyond policing.

As Garza put it to me, American society has turned to law enforcement to address the challenges Black communities face, but those challenges can’t be solved with a badge and a gun. “You don’t have schools that function well; you don’t have teachers that get paid; you don’t have hospitals in some communities,” she said. “You don’t have grocery stores in some communities. This creates the kinds of conditions that make people feel like police are necessary, but the solution is to actually reinvest in those things that give people a way to live a good life, where you have food, a roof over your head, where you can learn a craft or skill or just learn, period.”

Believing in racial equality in the abstract and supporting policies that would make it a reality are two different things. Most white Americans have long professed the former, and pointedly declined to do the latter. This paradox has shown up so many times in American history that social scientists have a name for it: the principle-implementation gap. This gap is what ultimately doomed the Reconstruction project.

One of the ways the principle-implementation gap manifests itself is in the distinction between civic equality and economic justice. After the Civil War, Representative Thaddeus Stevens, a Radical Republican, urged the federal government to seize the estates of wealthy former Confederates and use them in part to provide freedmen with some small compensation for centuries of forced labor. Stevens warned that without economic empowerment, freedmen would eventually find themselves at the mercy of their former masters.

“It is impossible that any practical equality of rights can exist where a few thousand men monopolize the whole landed property,” Stevens wrote in 1865. “The whole fabric of Southern society must be changed, and never can it be done if this opportunity is lost. Without this, this government can never be, as it never has been, a true republic.”

Even in his own party, Stevens’s idea was viewed as extreme. Nineteenth-century Republicans believed in an ideology of “free labor,” in which the interests of labor and capital were the same, and all workers could elevate themselves into a life of plenty through diligence and entrepreneurship. By arming Black men with the ballot, most Republicans believed they had set the stage for a free-labor society. They did not see what the emancipated saw: a world of state-sanctioned and informal coercion in which simply elevating oneself through hard work was impossible.

As the freedmen sought to secure their rights through state intervention—nondiscrimination laws in business and education, government jobs, and federal protection of voting rights—many Republicans recoiled. As the historian Heather Cox Richardson has written, these white Republicans began to see freedmen not as ideal free-laborers but as a corrupt labor interest, committed to securing through government largesse what they could not earn through hard work. “When the majority of the Southern African-Americans could not overcome the overwhelming obstacles in their path to economic security,” she wrote in The Death of Reconstruction, “Northerners saw their failure as a rejection of free-labor ideals, accused them of being deficient workers, and willingly read them out of American society.”

Retreating from Reconstruction, these Republicans cast their objections to the project as advocacy for honest, limited government, rather than racism. But the results would ultimately be the same: an abandonment of the freedmen to their fate. Men like Carl Schurz, who had been briefly radicalized by the violence in the South and the extremism of Andrew Johnson, began to see federal intervention on behalf of the freedmen as its own kind of tyranny.

“Schurz advocated political amnesty, an end to federal intervention, and a return to ‘local self-government’ by men of ‘property and enterprise,’ ” Eric Foner writes. “Schurz sincerely believed blacks’ rights would be more secure under such governments than under the Reconstruction regimes. But whether he quite appreciated it or not, his program had no other meaning than a return to white supremacy.”

Local authority was ultimately restored by force of arms, as Democrats and their paramilitary allies overthrew the Reconstruction governments through intimidation, murder, and terrorism, and used their restored power to disenfranchise the emancipated for almost a century. Many of the devices the southern states used to do so—poll taxes, literacy tests—disenfranchised poor whites as well. (It was not the first or last time that the white elite would see the white poor as acceptable collateral damage in the fight for white supremacy.) At the national level, the economic collapse brought on by the Panic of 1873 wounded Republicans at the ballot box and further weakened support for the faltering Reconstruction project.

White northerners deserted the cause as if they had never supported it. They understood that they were abandoning the emancipated to despotism, but most no longer considered the inalienable rights of Black Americans their problem.

“For a brief period—for the seven mystic years that stretched between Johnson’s ‘Swing Around the Circle’ to the Panic of 1873, the majority of thinking Americans of the North believed in the equal manhood of Negroes,” W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in 1935. “While after long years the American world recovered in most matters, it has never yet quite understood why it could ever have thought that black men were altogether human.” These Americans believed Black lives mattered. But only for a moment.

Thaddeus stevens knew that without sufficient economic power, civic equality becomes difficult to maintain. His insight has proved remarkably durable across American history. The question now is whether a new coalition, radicalized by racism, can defy that history.

The most dramatic advances for Black Americans since Stevens’s time have come in the form of civic equality, not economic justice. In 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt broke the party of Lincoln’s hold on northern Black voters with promises of a New Deal. But FDR’s reliance on southerners in Congress—the guardians of American apartheid—ensured that most Black Americans were discriminated against by the policies that built the prosperous white middle class of the mid-20th century: the Social Security Act, the National Housing Act, the GI Bill, and others.

When President John F. Kennedy introduced, in June 1963, what would become the Civil Rights Act, he saw it as fulfilling the work of Reconstruction. “One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free. They are not yet freed from the bonds of injustice. They are not yet freed from social and economic oppression,” Kennedy declared. “And this nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free.”

JFK’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, sought to enact his vision with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Fair Housing Act, in what is sometimes referred to as the Second Reconstruction. But just as the first Reconstruction had been obliterated by Jim Crow, the Great Society’s ambitions toward civic equality and economic justice were drowned by its crime-prevention programs. As the historian Elizabeth Hinton writes in From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, those programs metastasized into a bipartisan policy of mass incarceration. Future administrations from both parties divested from the Great Society’s social programs, while pouring funding into law enforcement. This, Hinton observes, left “law enforcement agencies, criminal justice institutions, and jails as the primary public programs in many low-income communities across the United States.”

Americans remember the occasion of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech as the March on Washington, but this is a shorthand: The 1963 event was actually called the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. King and others in the civil-rights movement did not see the goals of civic equality and economic justice as severable. Yet they, too, struggled to persuade white Americans to devote the necessary public resources to resolving the yawning economic disparities between Black people and white people.

“White America, caught between the Negro upsurge and its own conscience, evolved a limited policy toward Negro freedom. It could not live with the intolerable brutality and bruising humiliation imposed upon the Negro by the society it cherished as democratic,” King wrote in The Nation in 1966. “A hardening of opposition to the satisfaction of Negro needs must be anticipated as the movement presses against financial privilege.”

King was right. The racial wealth gap remains as wide today as it was in 1968, when the Fair Housing Act was passed. The median net worth of the American family is about $100,000. But the median net worth of white families is more than $170,000—while that of Black families is less than $20,000. According to William Darity Jr., an economist and Duke public-policy professor, fully a quarter of white families have a net worth of more than $1 million, while only 4 percent of Black families meet that threshold. These disparities in wealth persist among middle- and low-income families. In 2016, according to Pew, “lower-income white households had a net worth of $22,900, compared with only $5,000 for Black households and $7,900 for Hispanic households in this income tier.” These disparities are not the product of hard work or cultural differences, as one conservative line of thinking would have it. They are the product of public policy, what Darity calls the “cumulative damages” of racial discrimination across generations.

What economic strides Black Americans had made in the decades since 1968—largely through homeownership, the traditional cornerstone of wealth-building in the United States—were all but wiped out by the Great Recession of 2008. From 2005 to 2009, according to the Pew Research Center, the median net worth of Black households dropped by 53 percent, while white household net worth dropped by 16 percent.

Just as the Great Recession devastated the personal wealth of Black Americans, the coronavirus recession now threatens to destroy Black businesses, which are especially vulnerable to economic downturns, as they tend to lack corporate structures, easy access to credit, and large cash reserves. They are also less likely to be able to access government aid, because they may not have a preexisting relationship with the big banks that distribute the loans and because of outright discrimination. The National Community Reinvestment Coalition conducted an experiment in which white and Black subjects requested information about loans to help keep their small businesses open during the pandemic. It found that white requesters received favorable treatment—were offered more loan products, and were more likely to be encouraged to apply for them—compared with Black requesters.

From February to April, according to Robert Fairlie, an economist at UC Santa Cruz, 41 percent of Black businesses stopped operations, compared with 22 percent of businesses overall. This loss will have a cascading effect, devastating not only the business owners themselves but the people who live in the cities and neighborhoods where they are located. “Black-owned businesses tend to hire a disproportionate number of Black employees,” Fairlie told me.

In the aftermath of the coronavirus, the nation will have to be reconstructed. It will require a massive federal effort to keep Americans in their homes, provide them with employment, revive businesses that have not been able to function under pandemic conditions, protect workers’ health and safety, sustain cash-strapped state governments, and ultimately restore American prosperity. It will take an even greater effort to do so in a manner that does not simply reproduce existing inequities. But the necessity of post-pandemic rebuilding also provides an opportunity for a truly sweeping New Reconstruction, one that could endeavor to resolve the unfinished work of the nation’s past Reconstructions.

The obstacles facing such an effort are manifold. Too many Americans still view racism as largely a personal failing rather than a systemic force. In this view, one’s soul can be purged of racism by wielding the correct jargon, denouncing the right villains, and posting heartfelt Instagram captions. Fulfilling the potential of the current moment will require white Americans to do more than just seek or advertise their personal salvation.

Then there is the question of whether the political vehicle of today’s anti-racist coalition, the Democratic Party, is up to the task, should it prevail in the 2020 elections. Reversing the erosion of voting rights is an area of obvious partisan self-interest for Democrats, and one likely to command broad support. The fight against racist policing and mass incarceration is largely a state and local one. Activists have yet to persuade a majority of voters to embrace their most radical proposals, but they have already achieved a great deal of success in stiffening the spines of politicians in their dealings with police unions, in electing progressive district attorneys over the objections of those unions and their allies, and in prompting officials to transfer certain law-enforcement responsibilities to other public servants. The greater challenge will be enacting the kind of sweeping reforms that would unwind what King called entrenched financial privilege.

“Efforts to remedy glaring racial inequality in the criminal-justice system, which whites have long denied but now acknowledge, tap into principles of equal treatment that have historically been easier to get whites on board for than the big structural changes that are needed to produce some semblance of actual equality,” the political scientist Michael Tesler told me recently. “Whites have historically had little appetite for implementing the policies needed to achieve equality of outcomes.”

As for the Democrats’ presidential standard-bearer, Joe Biden has struck an ambitious note, invoking the legacy of Reconstructions past. “The history of this nation teaches us that in some of our darkest moments of despair, we’ve made some of our greatest progress,” Biden declared amid the Floyd protests in June. “The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth Amendments followed the Civil War. The greatest economic growth in world history grew out of the Great Depression. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of ’65 came on the tracks of Bull Connor’s vicious dogs … But it’s going to take more than talk. We had talk before; we had protest before. We’ve got to now vow to make this at least an era of action and reverse the systemic racism with long-overdue concrete changes.”

Such a call to action would be more promising if Biden himself were not an author of the system he now opposes. He became a U.S. senator in an era of racial backlash. He worked with segregationists to dismantle school-desegregation programs and was part of the bipartisan bloc that expanded mass incarceration. During the “tough on crime” era of the 1990s, he bragged on the Senate floor of the fondness for prisons and harsh punishment in the “liberal wing of the Democratic Party.” Biden’s selection of Kamala Harris as his running mate is historic, but Harris, a former prosecutor, is no radical on these matters.

Yet change is possible, even for an old hand like Biden. Ulysses S. Grant married into a slave-owning family, and inherited an enslaved person from his father-in-law. Little in his past suggested that he would crush the slave empire of the Confederacy, smash the first Ku Klux Klan, and become the first American president to champion the full citizenship of Black men. Before he signed the Civil and Voting Rights Acts as president, Senator Lyndon Johnson was a reliable segregationist. History has seen more dramatic reversals than Joe Biden becoming a committed foe of systemic racism, though not many.

If Democrats seize the moment, it will be because the determination of a new generation of activists, and the uniqueness of the party’s current makeup, has compelled them to do so. In the 1870s—and up through the 1960s—the American population was close to 90 percent white. Today it is 76 percent white. The growing diversity of the United States—and the Republican Party’s embrace of white identity politics in response—has created a large constituency in the Democratic Party with a direct stake in the achievement of racial equality.

There has never been an anti-racist majority in American history; there may be one today in the racially and socioeconomically diverse coalition of voters radicalized by the abrupt transition from the hope of the Obama era to the cruelty of the Trump age. All political coalitions are eventually torn apart by their contradictions, but America has never seen a coalition quite like this.

History teaches that awakenings such as this one are rare. If a new president, and a new Congress, do not act before the American people’s demand for justice gives way to complacency or is eclipsed by backlash, the next opportunity will be long in coming. But in these moments, great strides toward the unfulfilled promises of the founding are possible. It would be unexpected if a demagogue wielding the power of the presidency in the name of white man’s government inspired Americans to recommit to defending the inalienable rights of their countrymen. But it would not be the first time.

This article appears in the October 2020 print edition with the headline “The Next Reconstruction.”

* Lead image: Illustration by Arsh Raziuddin; photographs by Alex Lau; Earl Gibson III; Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times; Getty; Joe Raedle; Library of Congress; niAID; Zaid Patel