In recent years, the national political discourse in the US has been rocked by debate on the enduring impact of race and racism in society. Contentious and intense discussions have revolved around incidents of police-related violence against Black people (Bunn 2022); the content of educational curricula as part of a broader backlash against ‘critical race theory’ and ‘woke’ ideas (Mervosh 2023); and the dismantling of Confederate memorials, which remain widespread across the country (Ryckaert et al. 2020).

The revival of race as a core wedge issue in US politics is the latest stage in a saga that has permeated civil discourse and been at the centre of the country’s social divisions since its founding. Indeed, the history of the US is marked by racial conflict and struggle. The American Civil War (1861–65) brought about the end of slavery, yet Reconstruction failed to establish racial equality. Later, the civil rights movement of the 1960s dismantled most de jure forms of racial discrimination, yet stark disparities persist in critical areas such as education, housing, labour markets, and policing.

Much work has been done to understand the persistence of racial conflict and inequity in American society. For instance, recent research has shed light on ‘whitelashing’ (Logan 2023) and Jim Crow (Althoff and Reichardt 2023), and how they contributed to the failure of Reconstruction within the South.

In a new working paper (Bazzi et al. 2023), we provide fresh evidence on how exclusionary racial norms and institutions echoed across the country in the century after the Civil War. In particular, we document how the sprawling influence of ‘Confederate culture’ became a source of widespread and persistent racial animus and disadvantage in the US. This study offers insights into the historical roots of racial inequity in the US and its geography while providing novel, granular evidence on the role of culture and ideology in shaping institutions, power, and inequality.

Tracing confederate culture

After the Civil War, the ideological underpinnings of the Confederacy survived and reorganised in the South around the ‘Lost Cause’ mythology. The key elements of this narrative, aiming to redeem the image of the South, were crafted in an 1866 book by Edward A. Pollard, the director of a prominent newspaper in Richmond, Virginia. Lost Cause discourse glorified Confederate military figures and rationalised the war, painting the South in a positive light. It downplayed support for slavery as the cause of secession, highlighting Northern aggression against “states’ rights” instead. At the same time, the narrative was full of racist tropes, portraying enslaved Blacks as inferior and content, and slaveowners as generously paternalistic (Domby 2020, Esposito et al. 2021).

Our research shows how Confederate migrants diffused this ideology across the US. In the three decades following the Civil War, nearly one million Southern whites left the former Confederacy and settled throughout the rest of the US. This migration had widespread geographic scope, with migrants settling in many regions, including an overall push towards the West. There, they often went to young counties on the frontier, where institutions and cultural norms were malleable. The influence of the ‘Confederate diaspora’ in these places was more than just symbolic: decades later, Black residents there have relatively lower earnings, greater residential segregation, and higher rates of incarceration and police-induced mortality.

How could the Confederate diaspora have had such a persistent and harmful impact, even outlasting the removal of most de jure forms of racial discrimination in the 1960s? The answers, we contend, lie in culture and ideology, as embedded in local communities and institutions. Indeed, using modern survey data, we find that the historical presence of the Confederate diaspora predicts the intensity of racial animus and exclusionary attitudes toward Blacks today. To understand this story, however, we need to go back in time and trace the configuration and entrenchment of a particular expression of racial animus, rooted in US history.

To quantitatively characterise the historical configuration of Confederate culture outside the South and the role of the Confederate diaspora therein, we develop an ordinal index of Confederate culture that combines four key elements:

- Confederate memorialisation (Southern Poverty Law Center, n.d.)

- Chapters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy

- Chapters of the second Ku Klux Klan (VCU Libraries, n.d.)

- Lynchings of Black people (Seguin and Rigby 2019)

These expressions of Confederate culture in the early 20th century were highly interconnected. The United Daughters of the Confederacy supported the building of Confederate statues and other memorials, such as towns and streets named after Confederate generals (Cox 2003). And while the United Daughters of the Confederacy organised to diffuse Confederate symbols and win hearts and minds, the Ku Klux Klan mobilised to spread violent expressions of racial animus, which tragically included many episodes of lynchings of Blacks.

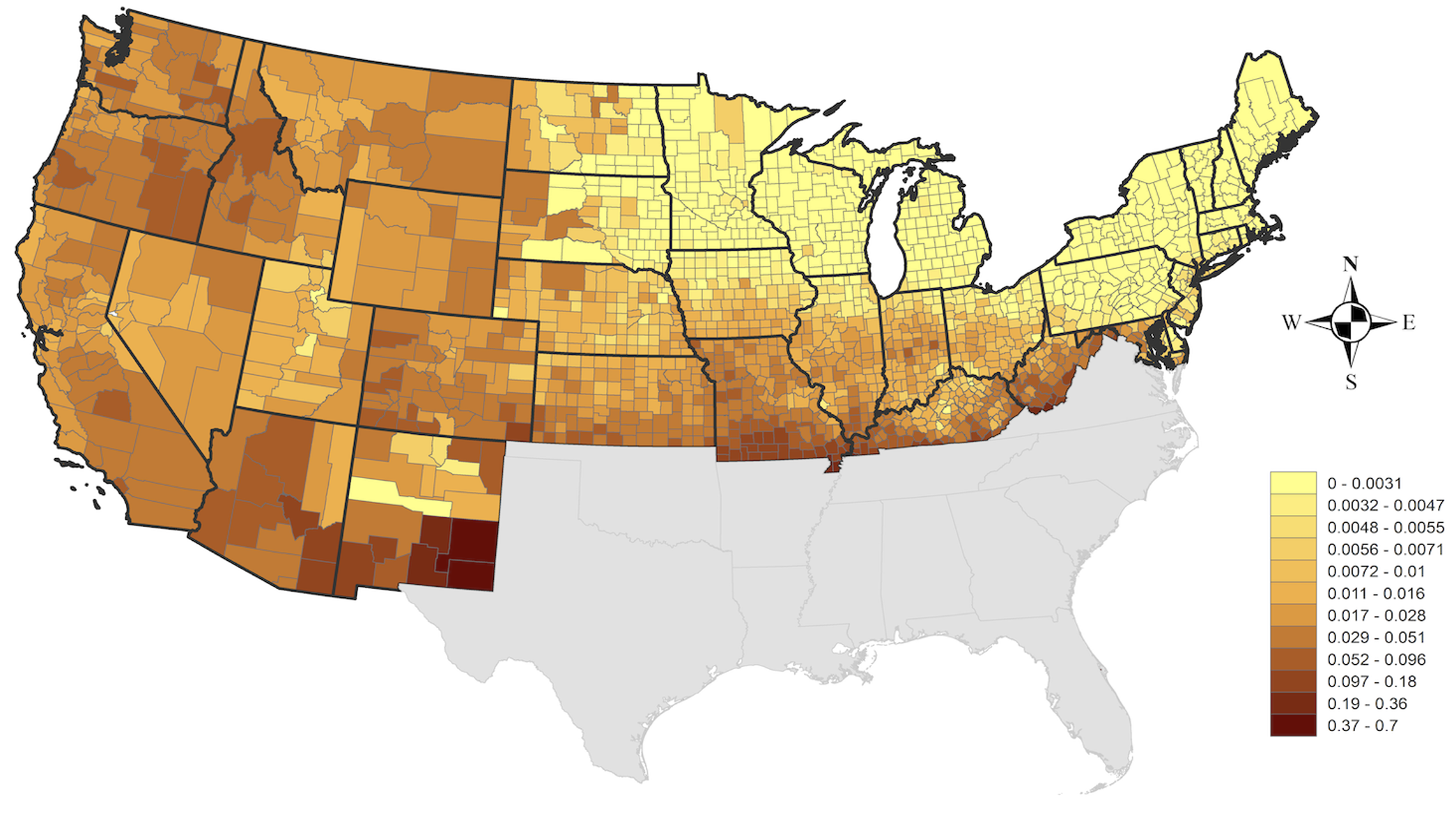

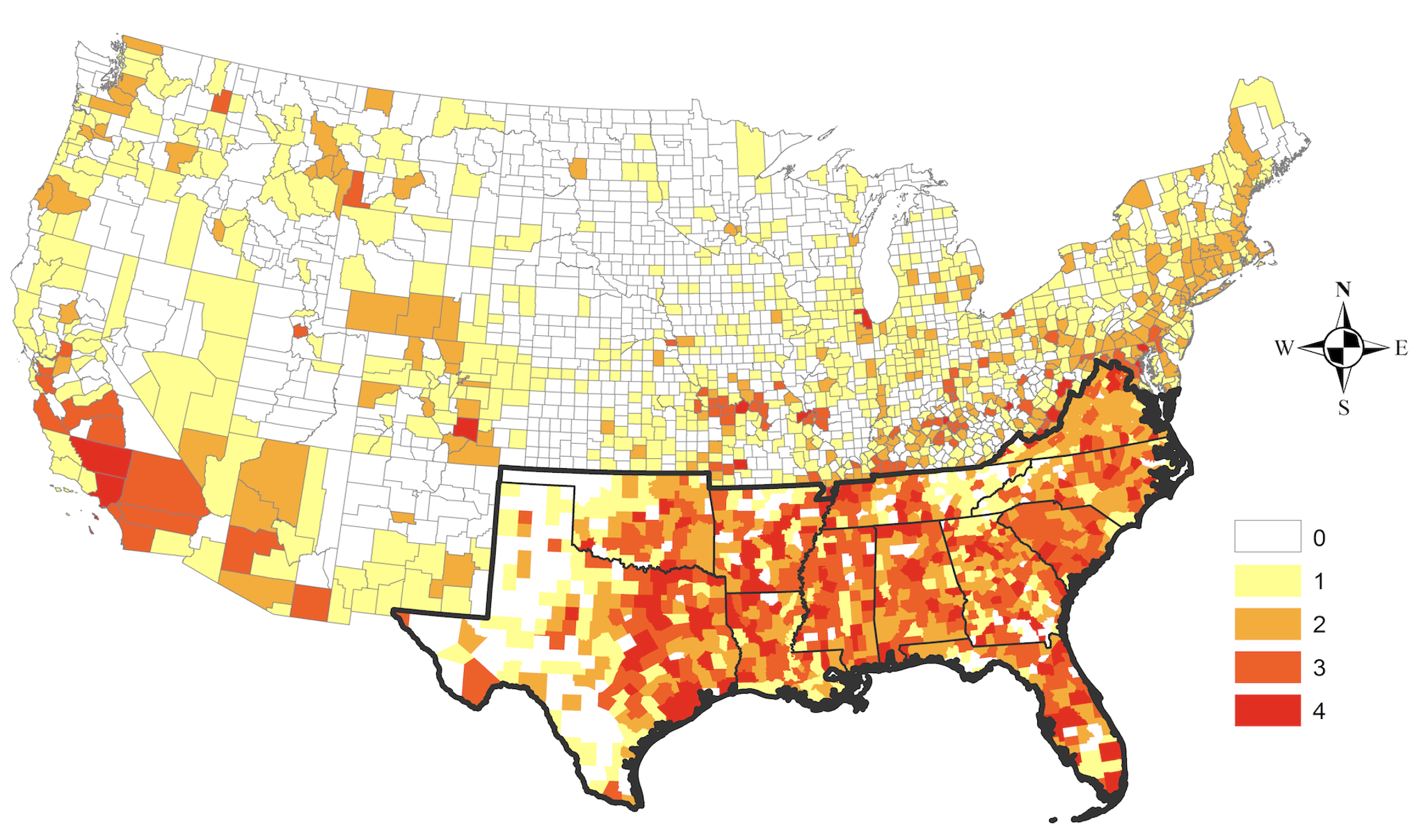

The spatial distribution of Confederate culture is shown in Figure 1, alongside the distribution of the diaspora. Note that, while Confederate culture was widespread in the South, it was not exclusive to it. Our study provides the first quantitative evidence – accounting for a wide array of other factors and addressing possible sources of bias – that post-bellum Southern white migration played a key role in shaping the geography of Confederate symbols and racial norms outside the South.

Figure 1 The Confederate diaspora and the diffusion of ‘Confederate culture’

(a) Per cent Southern whites in non-Southern counties, 1900

(b) Confederate culture index (United Daughters of the Confederacy, Confederate memorials, Ku Klux Klan, and lynchings)

Vehicles of cultural transmission

How did Confederate migrants exert such an outsized influence, dictating racial norms and entrenching racial inequity? Our study documents three underlying channels:

Local institutional capture

Southern-born migrants disproportionately worked in influential, public-facing occupations in their new communities, becoming judges, lawyers, public administrators, police, and clergy. We show that these choices did not merely reflect a desire for higher-income occupations but instead a distinct comparative advantage or ambition, as Southern whites sorted into positions of public authority, and their children did the same. Prominent examples of high-profile diaspora whites include Colorado governor Elias Ammons, Nevada governor John Sparks, California politician Cameron Thom, Oregon governor and senator George Chamberlain, and US President Woodrow Wilson, among numerous others.

Organisational mobilisation

The Confederate diaspora was key in the national expansion of the United Daughters of the Confederacy as well as the Ku Klux Klan. Besides documenting the county-level association between Southern white migration and the spread of the second Ku Klux Klan throughout the country, we conduct an in-depth analysis of the Klan in Denver, Colorado, a major hub of Klan activity in the 1920s for which complete chapter membership ledgers were recently uncovered and digitised.

We find that first- and second-generation Southern whites were overrepresented in the Ku Klux Klan. One such second-generation Southern migrant was Benjamin Stapleton. The grandson of a Confederate soldier and patriarch of a Colorado political dynasty, Stapleton ran for mayor of Denver with support from the Ku Klux Klan and governed the city, then a young and malleable locality, from 1923 to 1931 and 1935 to 1947. Through Stapleton, the Klan, which comprised almost 30% of the city’s white male adult population, was also able to gain control of the local police ( Goldberg 1981).

Cultural spillovers

Post-bellum migrants also transmitted their ideology to their neighbours. Across the country, non-Southern whites were more likely to name their kids after prominent Confederate leaders after moving to locations with a larger Confederate diaspora community. Returning to the Ku Klux Klan in Denver, we find that white men living next door to first- or second-generation Southern whites were significantly more likely to join the Klan themselves.

Our analysis also charts the micro-foundations of culture and local institutions, documenting heterogeneous effects that shed broader light on the nature of power, culture, institutions, and their malleability at critical junctures of political and economic development.

- We find particularly large effects of the diaspora where they sorted into positions of power, through which they had a direct and outsized influence on memorials, civil society organisations, and local institutions such as schools, the police, and the judiciary.

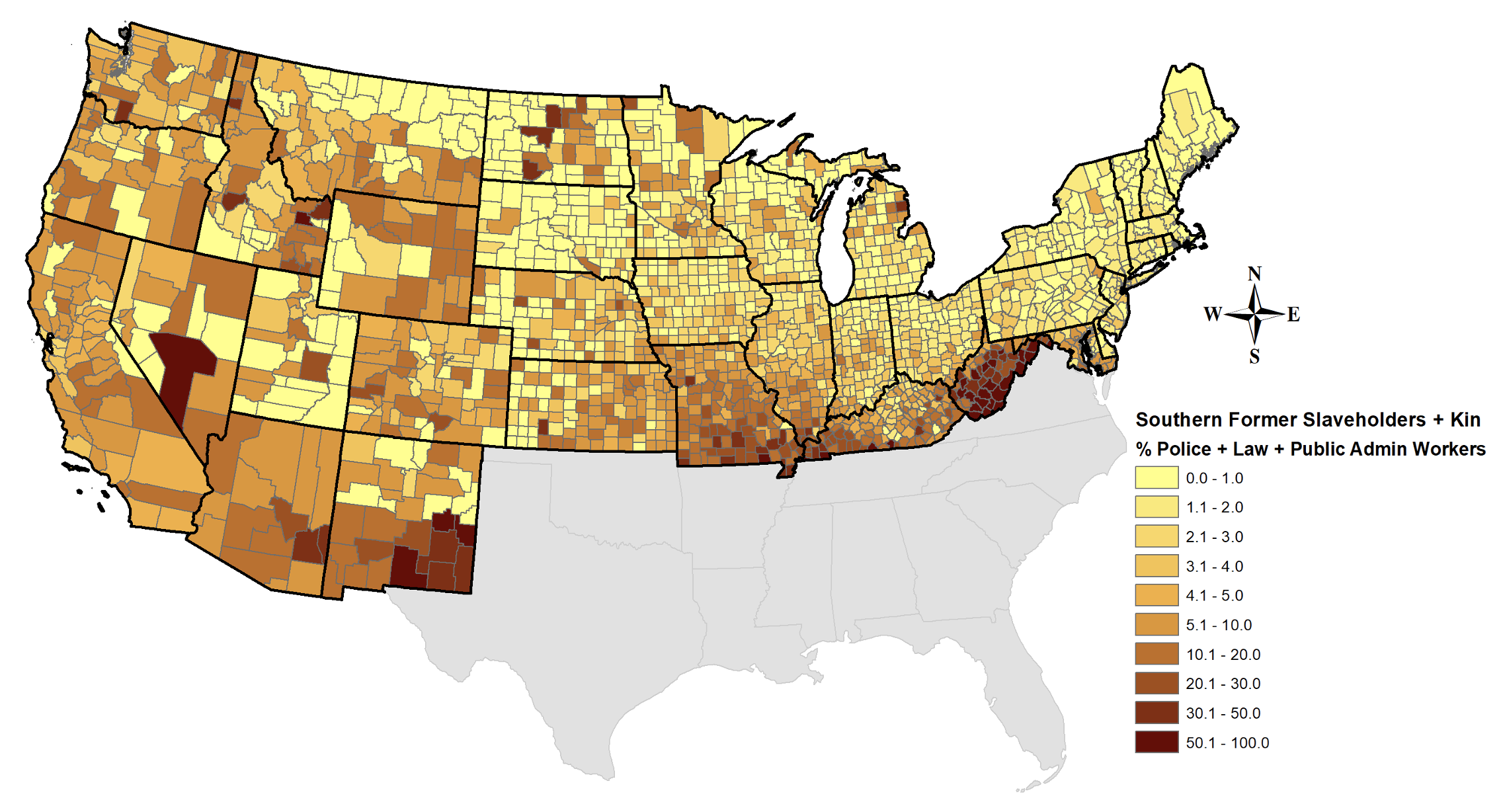

- The effects we find can be traced disproportionately to migrants who were former enslavers, who were even more overrepresented in positions of power at destination (see Figure 2). Such migrants may have had greater ambition to exert social control, stronger ideological attachments, or deeper grievances (Eli et al. 2018), given their direct involvement with enslavement, higher participation in the Confederate Army (Hall et al. 2019), and greater losses of wealth and power after the war (Ager et al. 2021).

- The impact of Confederate migrants was particularly outsized where culture and institutions were most malleable: when they settled in counties along the frontier, and where they found little resistance from non-Southerners who had served in the Union Army.

Figure 2 Per cent former Confederate slaveholders in governance, 1900

Together, these findings provide important insight into the historical roots of racial divisions found across the country still to this day.

References

Ager, P, L P Boustan, and K Eriksson (2021), “The intergenerational effects of a large wealth shock: White Southerners after the Civil War”, American Economic Review.

Althoff, L, and H Reichardt (2023), “Jim Crow and Black economic progress after slavery”, mimeo.

Bazzi, S, A Ferrara, M Fiszbein, T Pearson, and P A Testa (2023), “The Confederate diaspora”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18200.

Bunn, C (2022), “Report: Black people are still killed by police at a higher rate than other groups”, NBC News, 4 March 2022.

Cox, K L (2003), Dixie’s daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the preservation of Confederate culture, University Press of Florida.

Domby, A H (2020), The false cause: Fraud, fabrication, and white supremacy in Confederate memory, University of Virginia Press.

Eli, S, L Salisbury, and A Shertzer (2018), “Ideology and migration after the American Civil War”, The Journal of Economic History 78(3): 822–61.

Esposito, E, T Rotesi, A Saia, and M Thoenig (2021), “Memory and reconciliation: The dangers of common enemy narratives”, VoxEU.org, 23 May.

Goldberg, R A (1981), Hooded empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Colorado, University of Illinois Press.

Hall, A B, C Huff, and S Kuriwaki (2019), “Wealth, slaveownership, and fighting for the Confederacy: An empirical study of the American Civil War”, American Political Science Review 113(3): 658–73.

Logan, T D (2023), “Whitelashing: Black politicians, taxes, and violence”, Journal of Economic History 83(2): 538–71.

Mervosh, S (2023), “Florida’s new Black history standards have drawn backlash. Who wrote them?”, New York Times, 28 July.

Ryckaert, V, J L Mack, and C Hill (2020), “Confederate memorial removed from Garfield Park”, Indianapolis Star, 8 June.

Seguin, C, and D Rigby (2019), “National crimes: A new national data set of lynchings in the United States, 1883 to 1941”, Socius.

Southern Poverty Law Center (n.d.), “Whose heritage? Map”.

VCU Libraries (n.d.), “Mapping the Second Ku Klux Klan, 1915–1940”, Virginia Commonwealth University, website.

–Centre of Economic Policy Research, cepr.org

###