Chinese immigrants, escaped slaves, and Native Americans were all people U.S. forces tried to keep on one side or the other.

America’s southern border—which has shifted multiple times with U.S. expansion—was formed through violence. Texas and American militias used force to establish that border in the 1830s and 1840s, capturing modern-day states like California, Texas, and all of the American southwest from Mexico.

In the decades after, the both official and vigilante groups violently regulated the movement of people across that border—be they Native Americans, escaped slaves, Chinese immigrants, or Mexicans.

This policing wasn’t always aimed at keeping immigrants out. The Native Americans forced out of Texas had lived either in the area or further east before European colonizers violently pushed them West. Enslaved people from Africa were another group of non-immigrants whose movements vigilantes tried to police. Slave catchers who monitored the border weren’t trying to keep anyone out—they were trying to keep enslaved people in.

How the Current U.S.-Mexico Border Was Formed

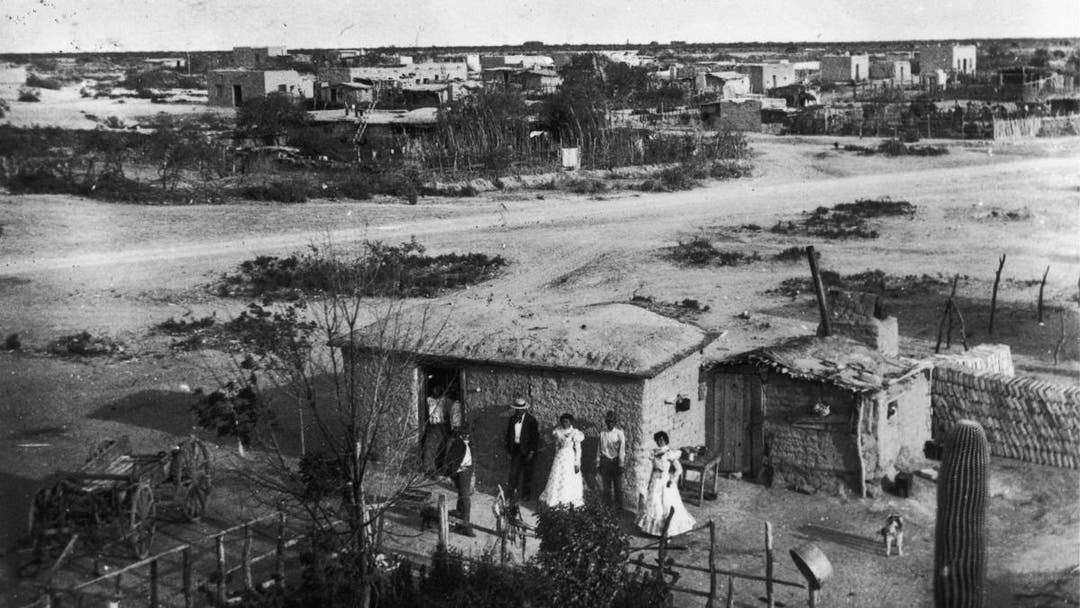

The U.S.-Mexican border was not always where it is today. When Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1821, the country’s territory included California, Texas, and the land in between. But in 1836, white Americans who’d moved to Mexico turned around and seceded from the country. They formed the short-lived independent Republic of Texas, which the U.S. annexed in 1845.

To maintain the borders of their new country, these self-declared Texans formed the Texas Rangers, also known as the Frontier Battalion. According to Miguel A. Levario, a history professor at Texas Tech, they were an early example of a group that used violence to maintain the border between Texas and Mexico. At that time, he says, “they were mostly responsible for removing Native Americans from west Texas.”

After the Mexican-American War, the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo transferred 55 percent of Mexico’s territory to the United States, establishing (more or less) the same borders that the countries have today.

Before Immigrants, U.S. Forces Policed the Border for Escaped Slaves

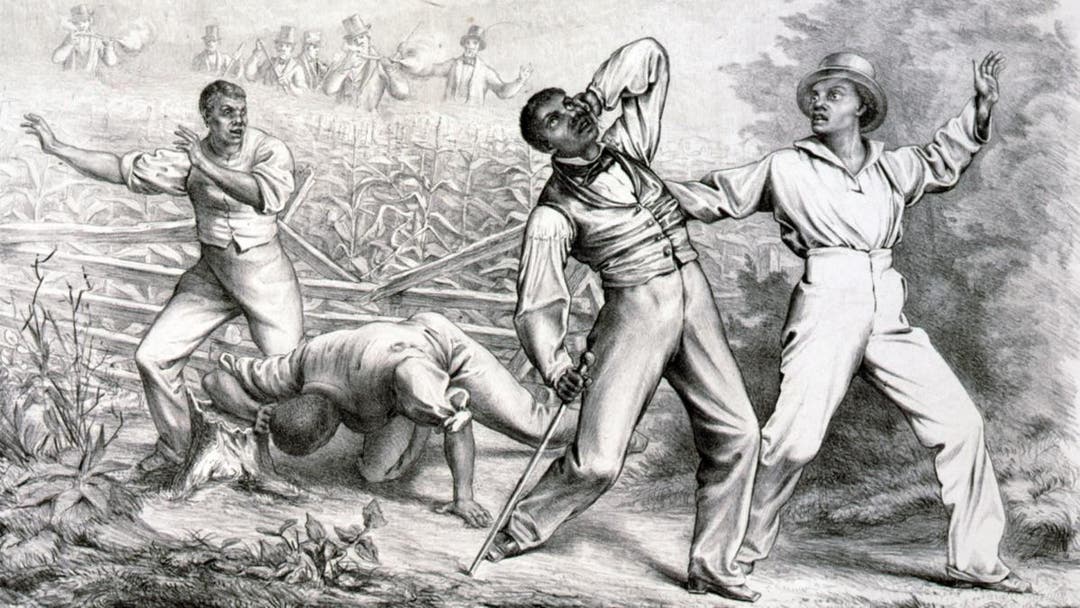

The same year that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo cut Mexico in half, the Fugitive Slave Act ushered in a new kind of violent border control.

After Mexico ended slavery between 1829 and 1830, the Texans re-established it in the new Republic of Texas. By the time the U.S. annexed the territory, its enslaved population had grown from 5,000 to 30,000.

For many enslaved people, fleeing south to Mexico—which was closer to many slave states—made more sense than trying to make it to the northern free states. But after the Fugitive Slave Act established that, legally, slaves must be returned to their owners, vigilante slave catchers began to monitor the U.S.-Mexican border in the hopes of earning a reward for capturing escapees.

Using the Border to Keep “Illegal” Immigrants Out

The first federal law governing which immigrants could and couldn’t enter the U.S. was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. With it, Chinese immigrants became “the earliest targets of systematic efforts to only selectively allow admissions,” says Madeline Y. Hsu, a history professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

“You had to be part of [these] very limited exempt classes, which included people like students, merchants, the merchants’ family members, diplomats,” she says. Chinese immigrants who didn’t meet these standards began to enter the country Canada and Mexico; a type of U.S. immigration that was, for the first time, “illegal.”

These immigrants began to enter mostly through Mexico in the late 1880s, after Canada passed a tax on Chinese immigration. And because of this, the U.S. began to focus more heavily on the U.S.-Mexican border as a place where immigration officials needed to screen people to determine if they could enter.

Targeting Mexican Immigrants

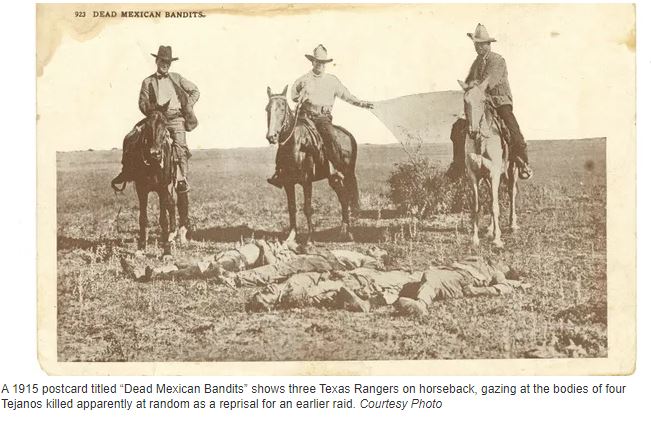

Even with this increased attention to the border, there was no concerted effort to keep Mexicans from migrating to the United States until the Mexican Revolution broke out in the 1910s. At first, U.S. armed forces monitored the border to keep violent revolutionary conflicts from spilling over the border. However, once Mexicans began to escape the conflict by immigrating to the U.S. in large numbers, other militias formed along the border to keep them out—including the Texas Rangers, who were still an organized military force.

“The rangers were very much part of violence toward the indigenous Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the 1910s,” Levario says. In addition, Texas vigilantes known as “home guards” began to guard the border. Although these home guards weren’t official state forces, they still had “the blessing of the governor to operate,” he says.

In 1924, the U.S. established the Border Patrol, a federally armed force specifically dedicated to policing the border year-round. Initially, these officers did more policing of Prohibition-era bootleggers than Mexican immigrants. But like the forces of the 1910s, its main goal was to impede Mexican immigration, as well as unauthorized immigration from Asian countries.

In “almost exactly 100 years,” Levario notes, “our approach to border security with Mexico has not really evolved.” But it has expanded greatly. Policing America’s borders is now a $4 billion per-year enterprise, requiring some 20,000 Border Patrol agents.

–history.com