BEAUFORT — When they were students at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in the 1970s, Ben Hodges and Chris Allen learned a lot about the country’s various armed engagements.

Many years later — after Hodges retired as a three-star lieutenant general of the Army, after Allen retired from a career in the Special Forces — they discovered a void in their knowledge of U.S. military history.

No one told them much about African American contributions before World War II. Those contributions dated to the Colonial period and, given the widespread and profound impacts of the institution of chattel slavery, were quite significant.

They learned that Black people fought on both sides of the Revolution, but mostly on the British side since a Patriot defeat would have spelled the end of slavery. They learned that Black people fought in the War of 1812, often hoping to take advantage of an offer by the King to relocate to England and be free. And some participated in the 1846-48 expansionist Mexican-American War.

But such service was sporadic, often frowned upon by White leaders, and not always officially sanctioned.

Then they learned about the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, organized in Beaufort in 1862.

“This marks the beginning of continuous service by African Americans in the U.S. Army,” Hodges said. And that service was high-risk and noteworthy.

Now the two friends are pushing for their alma mater — and for other institutions — to place greater emphasis on the history of African Americans’ military service. And they want the 1st South to get some kind of formal recognition.

“We are looking out for the legacy of these anonymous soldiers,” Allen said.

‘Onto something’

Allen, who had achieved the rank of colonel, settled in the Beaufort area in 2012 to enjoy an active retirement. Interested in history, he volunteered to be a docent at the Beaufort History Museum located at the old Arsenal downtown. A paper written by high school student Andy Holloway, whose mother trained Allen in museum pedagogy, opened his eyes to the 1st South.

Allen was embarrassed he hadn’t heard anything about this Black regiment before, so he started to do his own research, he said.

“We know African Americans served in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, but it was against the law from 1792 on for African Americans to join the armed forces,” he said.

It was against the law because White people feared that permitting Black people to carry arms could lead to violent rebellion and the overthrow of the slave economy.

Allen contacted Hodges and the two friends discussed the matter. Hodges became similarly intrigued by this history and, being a three-star general, was someone others tend to regard.

They wanted to know: Were they merely ill-educated yokels pursuing a line of inquiry that others, including professional historians, had already mined? Or was this a worthy intellectual expedition that could help illuminate an important part of the past?

Hodges called someone he knew at West Point, Brig. Gen. Ty Seidule, head of the history department, and asked for a reality check.

Yup, Seidule said, this part of military history is too little known.

“It gave us some confidence that we were onto something,” Allen said.

What they were onto was a remarkable effort on the part of hundreds of enslaved people suddenly liberated from bondage in the Beaufort area to help the Union wage war against those whose goal was to protect the institution of slavery.

The risk they assumed was enormous. In 1862, no one knew what the outcome would be, and everyone knew they were getting themselves into something ugly and bloody. If a White Union soldier was captured, he might survive his ordeal and eventually return to civilian life; if a Black fighter was captured, he could be sure about his fate: reenslavement (or worse). And it was likely he would never see his family again.

When Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, heard about the 1st South, he declared that any captured members of the regiment would not be considered prisoners of war. Rather, they would be treated as runaway slaves and sold at auction. Any White officers taken prisoner would be hanged.

But for many, the hope for freedom outweighed everything else.

In November 1861, Union troops took control of Port Royal Sound and created a base of operations in the Southeast. Local White property owners in the town of Beaufort and in its surrounding countryside fled. Suddenly, about 10,000 enslaved people were emancipated by default. Union administrators weren’t sure about what they should do.

Maj. Gen. David Hunter, commander of the Army’s Department of the South, assembled a regiment of 500 Black men in March 1862 but lacked the required political support to maintain it. Meanwhile, Frederick Douglass and Robert Smalls were in Washington, D.C. around this time to argue the merits of enlisting African Americans in the Union Army.

On Aug. 25, President Abraham Lincoln authorized the establishment of a Black regiment.

About 1,000 Black men, some who escaped enslavement, volunteered to sign up. The enterprise, led initially by Gen. Rufus Saxton, was experimental, for White people tended to doubt the abilities or the intentions of their Black neighbors. But this conflict was likely to become a war of attrition, for which many soldiers would be required. Union leaders knew they needed all the help they could get.

‘A powerful symbol’

That wasn’t the only thing Lincoln did that year regarding enslaved Black people. Based in some measure on Hunter’s efforts, the president determined to issue an Emancipation Proclamation. He would announce his intentions in September, then proclaim on Jan. 1, 1863, that “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

The members of the 1st South assembled on Port Royal Island that New Year’s Day to hear the proclamation read aloud.

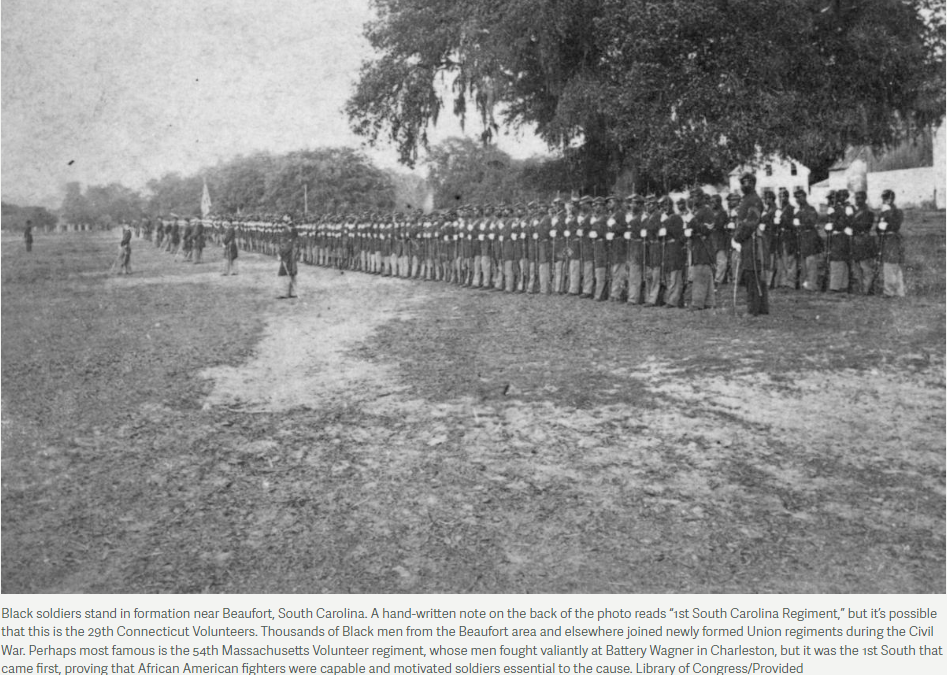

By then, Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson had arrived to assume command of the regiment. It’s thanks in large part to Higginson, a writer and abolitionist who kept a diary of his experiences in Beaufort, that we know about the 1st South. Documentation is otherwise scarce. An African American nurse, Susie King Taylor, published in 1902 a memoir called “Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers” in which she recounted her close association with members of the 1st South (later renamed the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops). One or two photographs survive of the regiment. That’s about it.

Port Royal served as the Union’s main base of operation in the region, and its strategic value could not be overstated. Here, the United States recruited fighting men; here it set up agencies and hospitals; here it managed deployments to other parts of the South; here it coordinated its logistical efforts, such as importing and exporting supplies.