In a recent research visit to the Emily Dickinson museum and archives in Amherst, I chanced upon a most improbable discovery of forgotten, pioneering work by another titan of culture.

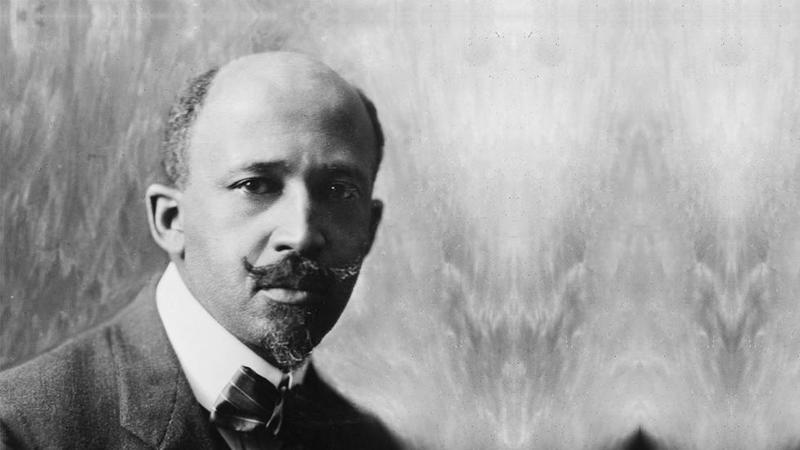

When thirty-one-year-old W.E.B. Du Bois (February 23, 1868–August 27, 1963) heard that the World’s Fair to be held in Paris in 1900 would include a special exhibition on the subject of sociology, he saw in it an opportunity to open the world’s eyes to what had been occupying him for nearly a decade — “the American Negro problem.” In The Autobiography of W.E.B. Dubois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century (public library), he recounts:

I wanted to set down its aim and method in some outstanding way which would bring my work to notice by the thinking world.

Since he became the first African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard, Du Bois had amassed a formidable set of statistics on the socioeconomic plight of black people in America in the decades since the transition from enslavement to freedom. But Du Bois had one pressing problem: How would he make statistics fit for an exhibition and compelling enough to compete for attention with such marvels of invention and showmanship as the talking films, panoramic paintings, escalators, and world’s largest refractor telescope, all of which made their debut at the 1900 Paris Exposition?

He decided to visualize his data in a series of artful, striking diagrams that beckon both the intellect and the imagination, dispelling sociocultural misconceptions with statistics in a viscerally arresting way — a way “to give, in as systematic and compact a form as possible, the history and present condition of a large group of human beings.”

During the Crimean War half a century earlier, Florence Nightingale had effected major political reform in healthcare through a pioneering use of data visualization. She designed a new type of pie chart, known today as the Nightingale rose diagram, comparing mortality rates across time in a simple, elegant histogram, which she sent to Queen Victoria as viscerally unambiguous proof of the effectiveness of her sanitation strategy.

Being exceedingly well read and indiscriminately interested in various disciplines related to social reform, Du Bois was very likely aware of Nightingale’s revolutionary visualizations of statistics. With the Paris Exposition approaching, he enlisted some of his best students in rendering his statistics on four key dimensions of the black experience — “the history of the American Negro,” “his present condition,” “his education,” and “his literature” — into a series of hand-painted ink and watercolor charts, diagrams, and figures. Du Bois took great pride in the project, conceived of and created entirely by African Americans:

We have [made] an honest, straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.

This they accomplished in very little time and with no funding. By the end, Du Bois found himself “threatened with nervous prostration” and unable to afford proper passage to Paris, so he purchased the cheapest possible ticket and traveled in steerage in the belly of the ship. Upon arrival, he found himself “astonished to see automobiles on the streets; not many but perhaps a dozen in a day.” He recalled in his autobiography:

I lived to see the jokes about the possibility of these motors displacing the horse fade away and automobiles fill the streets and cover the nations.

Amid the spectacle of astonishments, he presented thirty-two charts, 500 photographs, and a variety of maps, mounted on two-by-three-foot hinged boards that fanned out from the walls of the 20-square-foot exhibition hall — inventive visualizations of data reminiscent of Victorian mathematician Oliver Byrne’s stunning 1847 illustrations of Euclid’s Elements and Goethe’s graphically daring diagrams of color and emotion. Aesthetically, Du Bois’s visualizations evoke the iconic abstract paintings of Piet Mondrian and the pioneering color-block sculptures of Anne Truitt, but predate the influence of both by half a century away.

The exhibition was an unexampled success, earning Du Bois a gold medal in the Paris Exposition and attracting coverage from major newspapers, both black and white, in Europe and America. “This is the first time in the history of exposition abroad that the Afro-American has ever taken so important and successful a part,” exclaimed the Saint Paul Appeal in October of 1900, seeing in Du Bois’s exhibition “proof that all classes of [the American] population are prosperous, progressive, and valuable citizens.” The project would go on to shape how Du Bois himself thought about sociology, informing the ideas with which he would set the world ablaze three years later in The Souls of Black Folk.

Complement with Du Bois’s magnificent letter of life-advice to his young daughter and his correspondence with Einstein about social justice, then revisit Alan Turing’s little-known biology diagrams and Giorgia Lupi’s hand-drawn visualization of great writers’ sleep habits and literary productivity.

Data images via The Library of Congress

–themarginalian.org