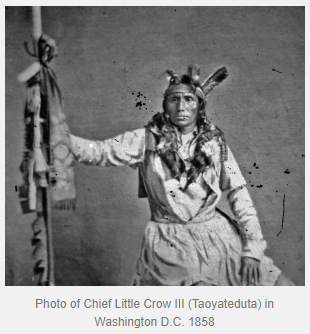

Many (Emerging Civil War) readers will know (and perhaps take delight in the fact) that Major General John Pope was banished to Minnesota in the wake of his disastrous defeat at the battle of Second Bull Run. President Abraham Lincoln asked Pope to go west and oversee the aftermath of what Civil War-era Americans termed the “Dakota Uprising.” Scholars today view the events of the late summer of 1862 as a far more complex event than nineteenth-century Americans. Historians now opt against incendiary language like “uprising” or “massacre” and prefer to see the resistance movement of Mdewakanton Dakota leader Little Crow as a strike against American expansion and a significant moment in Native American resistance to US settler colonialism.

Reevaluating language is one way that scholars have sought to resituate the events of the late summer of 1862 within the broader context of the Civil War. Another has been to look at the theater inherited by Pope as a zone of military crisis and contestation. Had Pope gotten his way, it may also have been a site for turning the war between North and South into an international conflagration. Because, in his effort to respond to the successful resistance of Little Crow and his adherents, Pope proposed invading Canada, pursuing the Native peoples who had evaded capture and a military tribunal. Pope believed that crossing the border would put an end to Native American threats to white settlements in Minnesota and the Dakota Territory, by demonstrating that international borders would no longer function as deterrents to US military power. Fortunately for Pope (and his already suspect military reputation), the arguments against such an action were equally compelling and Pope stayed put on the southern side of the 49th parallel.

Reevaluating language is one way that scholars have sought to resituate the events of the late summer of 1862 within the broader context of the Civil War. Another has been to look at the theater inherited by Pope as a zone of military crisis and contestation. Had Pope gotten his way, it may also have been a site for turning the war between North and South into an international conflagration. Because, in his effort to respond to the successful resistance of Little Crow and his adherents, Pope proposed invading Canada, pursuing the Native peoples who had evaded capture and a military tribunal. Pope believed that crossing the border would put an end to Native American threats to white settlements in Minnesota and the Dakota Territory, by demonstrating that international borders would no longer function as deterrents to US military power. Fortunately for Pope (and his already suspect military reputation), the arguments against such an action were equally compelling and Pope stayed put on the southern side of the 49th parallel.

In May of 1864, the Member of Parliament for King’s County, Ireland rose in the House of Commons to deliver a speech on the “Outrages by Sioux Indians” taking place in the Red River settlement of Canada. The settlement—what is today the Canadian province of Manitoba—like all of Canada in 1864, remained under the direct control of the British government.

The speech that John Hennessy delivered emphasized the difficulty Indigenous incursions into the Canadian settlements might cause the British government. The MP predicted depredations that might result in thousands of men, women, and children killed. In spite of their exaggerated fears, the British government also realized that allowing the United States Army to invade and occupy the British possessions would set an undesirable precedent and leave their far western territories. Despite wanting to help the citizens of Canada, Hennessy urged his government not to leave their Canadian provinces, “at the mercy of a foreign soldiery.”[1]

Indigenous use of the border between the United States and Canada laid bare the delicate balance of international power on the North American continent. Historians have long argued that this balance of power was endangered by the Civil War, particularly in Mexico, where a wary eye was always trained Napoleon III’s French puppet government. The results of a war with the British in Canada, provoked by Native actions, would likely have major ramifications for the future of the North American continent.

The citizens of British North America had their own concerns about the effect the Civil War would have on their territory. If the Confederacy succeeded in establishing an independent nation, “the North [might] seek compensation in the conquest of British America.”[2] If the Union succeeded in putting down the Confederate rebellion, the prospects were not any more encouraging. British North Americans that the victorious Union “might attack the provinces in order to employ war-hardened troops, to complete the work of Manifest Destiny.”[3] The prospect of Union victory convinced many that the restored United States would have the resources to dominate the continent and exclude British North America from trans-Atlantic (and trans-Pacific) trade.

But the officials on either side had little recourse. Indigenous use of the border had only increased after the events of 1862 and left policy makers and military officials grasping for options. Secretary of State William H. Seward sent a brief letter to Lord Lyons, the minister to United States from Great Britain, on January 12, 1863, “with a view to prevent, if possible, hostile Indians residing on either side of the frontier from being supplied with arms, ammunition, or military stores, to be used against the peaceful inhabitants of the United States.”[4] The letter helped little. General Henry H. Sibley wrote from St. Paul on January 25, 1864, that “the hostile Indians are directly aided and abetted by Her Majesty’s subjects.” He told the commander of the Department of the Northwest, General John Pope, that he hoped that a “professedly friendly power shall not longer permit its soil to be a convenient refuge for these Ishmaelites of the prairies.”[5]

The British had offered to provide subsistence and supplies to the Indigenous refugees, on the condition that they should only be used for hunting game—and that the Natives would return to the American side of the border. Governor Alexander Dallas, of the Red River Settlement, hoped for a speedy evacuation from his province. Dallas’s requests to London for regular British troops to defend the border had been denied—and he could not protect his constituents without aid. And yet, when the governor met with his council on January 24, 1864, he was forced to report that the Santee “had gone no further than White Horse Plain, with the avowed intention of remaining there.” Dallas further reported that he was “now disposed strongly to doubt, whether, they had really ever intended to leave the Settlement this Winter.”[6]

As Dallas fretted, Pope proposed to send US troops across the border after the Santee. Despite the perceived threat coming from Canada, both General in Chief Henry Halleck and President Abraham Lincoln were less than inclined to agree to the plan. In response to a request for instructions on the situation, Halleck informed Pope: “The President directs that under no circumstances will our troops cross the boundary line into British territory without his authority.”[7] Though by 1864 British intervention on behalf of the Confederacy no longer seemed likely, Lincoln still urged caution when it came to the war’s international aspects.

John Pope wanted to invade Canada. His wishes were denied. But “What-If” he had gotten his way? Several potential results come to mind. First, the British may have reevaluated their position vis a vis neutrality. Second, had the Americans been adamant about the need to pursue the Santee across international borders, the British Crown may have been forced to provide troops to support the mission or to protect their own citizens from a foreign invader.

And, had the British actually sent support to their western Canadian frontier, the British citizens living in Canada may have been contented with the idea that Parliament had their safety and security at heart. One of the primary reasons that British Canadians pursued Confederation and greater independence from Great Britain in 1867, after all, was the failure of the Crown to provide for its North American settlers, in their moments of greatest danger.

[1] HANSARD, House of Commons Debates, May 3, 1864, Volume 174, Reference Number cc2053-5.

[2] W.L. Morton, “British North America and a Continent in Dissolution, 1861-71,” History, Volume 47, Issue 160 (January, 1962):148.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Message of the President of the United States, and Accompanying Documents, to the Two Houses of Congress, at the Commencement of the First Session of the Thirty-Eighth Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1863), 492.

[5] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 127 vols. index and atlas [Washington: GPO, 1880-1901], ser. 1, 34[2]:152-3

[6] Edmund Henry Oliver, ed., The Canadian North-West, Its Early Development and Legislative Records; Minutes of the Councils of the Red River Colony and the Northern Department of Rupert’s Land (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1914), p. 533.

[7] O.R., 22[2]:211.

–emergingcivilwar.com