The dentist was a few minutes late, so I waited by the barn, listening to a northern mockingbird in the cypress trees. His tires kicked up dust when he turned off Drew Ruleville Road and headed across the bayou toward his house. He got out of his truck still wearing his scrubs and, with a smile, extended his hand: “Jeff Andrews.”

The gravel crunched under his feet as he walked to the barn, which is long and narrow with sliding doors in the middle. Its walls are made of cypress boards, weathered gray, and it overlooks a swimming pool behind a white columned house. Jeff Andrews rolled up the garage door he’d installed.

Our eyes adjusted to the darkness of the barn where Emmett Till was tortured by a group of grown men. Christmas decorations leaned against one wall. Within reach sat a lawn mower and a Johnson 9.9-horsepower outboard motor. Dirt covered the spot where Till was beaten, and where investigators believe he was killed. Andrews thinks he was strung from the ceiling, to make the beating easier. The truth is, nobody knows exactly what happened in the barn, and any evidence is long gone. Andrews pointed to the central rafter.

“That right there is where he was hung at.”

Emmett till was killed early on the morning of August 28, 1955, one month and three days after his 14th birthday. His mother’s decision to show his body in an open casket, to allow Jet magazine to publish photos—“Let the world see what I’ve seen,” she said—became a call to action. Three months after his murder, Rosa Parks kept her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, and she later told Mamie Till that she’d been thinking of Emmett when she refused to move. Almost 60 years later, after Trayvon Martin was killed, Oprah Winfrey channeled the thoughts of many Americans in evoking the memory and the warning of Emmett Till.

But the way Till’s name exists in the firmament of American history stands in opposition to the gaps in what we know about his killing. No one knows, for instance, how many people were involved. Most historians think at least seven were present. Only two were tried: half brothers J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant. Another half brother, Leslie Milam, was there that night too. He lived in an old white farmhouse a few dozen steps from the barn, next to where Jeff Andrews’s house now stands.

In 1955 an all-white, all-male jury, encouraged by the defense to do their duty as “Anglo-Saxons,” acquitted J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant. Because the defendants couldn’t be tried again, they got paid to make a confession to a national magazine—a heavily fictionalized account stage-managed by their lawyers—and Leslie Milam and his barn were written out of the story. Ask most people where Till died and they’ll say Money, Mississippi, the town where Till whistled at Bryant’s wife outside the family’s store. An Equal Justice Initiative monument in Montgomery says Money. Wikipedia does too. The Library of Congress website skips over the barn, which is just outside the town of Drew, about 45 minutes from the store.

I learned about the barn last year and have since made repeated visits, alone and with groups, once with members of Till’s family. Over and over, I drove from my home in the Mississippi hill country back into the gothic flatland where I was born. The barn’s existence conjures a complex set of reactions: It is a mourning bench for Black Americans, an unwelcome mirror for white Americans. It both repels and demands attention.

During one of my visits, Patrick Weems sat next to me as I navigated the backroads near Drew. A young, white Mississippian, Weems co-founded the Emmett Till Interpretive Center in nearby Sumner, to commemorate the places where Till spent the last days of his life. Weems is now working with Wheeler Parker, Till’s cousin and the last living eyewitness to the kidnapping, to create a series of monuments in Chicago, where Till grew up, and in Mississippi, where he died, with the hope that they might one day form a new national park. That’s why the barn matters now. There’s money, energy, urgency bearing down on the dentist and the long cypress building overlooking his pool, which is made somehow more menacing by the way it just sits there, unmemorialized.

One afternoon Weems and I were a little lost, surrounded by an endless landscape of soybeans and corn. I made a wide right turn around a cornfield and there it was, ordinary and freighted, hunkered in the flat, hot sun.

“Here we are,” Weems said. “Ground zero.”

Wheeler parker made that same ride not long ago. He looked out the window of a bus at overflowing rivers and submerged farmland. It would not stop raining. The flood, perhaps mercifully, prevented the bus from reaching the barn. Parker sat quietly while Weems and a group of architects and planners—part of a team charged with imagining the memorials—got out and stared across the unruly bayou at the barn.

When everyone climbed back on the bus, the air felt somber. Parker didn’t say much. He thinks about Till every single day, and not as a symbol or a part of American history. Parker was Till’s cousin, yes, but also his best friend. They rode bikes together. Parker is 82 years old now and wants to see a memorial to Till built before he dies. Over and over, he told the people on the bus how much things had changed in Mississippi, so many times that it sounded like the person he was trying most to convince was himself. Maybe that’s why he keeps coming back here to tell this story, because he knows that all the changes he’s seen remain fragile.

For white Mississippians like Jeff Andrews and me, it’s possible to grow up rarely, if ever, hearing Emmett Till’s name. Slipping free of the generational guilt and shame of this particular murder—a proxy for so many acts of violence and cruelty, large and small—remains a central part of a white child’s education in the Delta, where a system of private schools arose in response to integration. “Seg academies,” they’re called. A Mississippi-history textbook taught at one in the early 1990s didn’t mention Till at all. A newer textbook contains 70 words on Till, calling him a “man” and telling the story of his killing through the lens of the damage that two evil men, J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant, did to all the good white folks. Half the passage is about how the segregationist governor was a “moderating force” in a time when media coverage of Till’s murder “painted a poor picture of Mississippi and its white citizens.” This textbook is still in use.

Jeff Andrews says he doesn’t feel personally connected to Till’s death. He didn’t know the history of his barn when he bought the property back in 1992, but now he understands its importance, and the emotional power it holds for the Till family members he welcomes on his land. Most everyone, from his patients to national civil-rights scholars, likes and respects Andrews. He winces a little when he sees people noticing his Christmas decorations. “I hate to have to show people this,” he says, “because I got so much shit in here.”

After he showed it to me, we found a place to sit in the shade by his pool. I kept looking back at the barn. He knew what I was doing.

“We don’t think about it,” Andrews said. “It’s in the past.”

Out by the barn, his yellow lab, Dixie, rolled in the hot grass near the corn.

Emmett till had looked forward to his trip south from the moment his mother gave him permission to go. He was too young to understand that he was arriving in a place with a violent history just as that place was dying. For two centuries cotton had been as central to the global marketplace as oil is today, fueling commerce and war and suffering. But by 1955 the cotton economy, and the caste system sustained by it, was in a downward spiral.

A year before Till traveled to Mississippi, the Supreme Court outlawed “separate but equal” in Brown v. Board of Education. Mississippi and other southern states refused to comply, so the Court issued another ruling saying that they had to desegregate the public schools. Cotton prices were stagnant. Banks were calling in loans. A drought set in. Small-time operators like Leslie Milam couldn’t afford to irrigate, so already thin crops just burned in the fields. Several years without a lynching in the state ended in May 1955 when a civil-rights activist and preacher named George Lee was murdered. On August 13, a voting-rights activist named Lamar Smith was killed in Brookhaven. Seven days later, Emmett Till and his older cousin Wheeler Parker left Chicago on a southbound train.

Parker told me he remembers how much Till bounced around the train, bothering people with his nervous energy. His mother, whose family had fled the Delta three decades earlier, had tried to prepare him for the unwritten but ironclad rules that would govern his time in Mississippi. Say “Yes, sir” and “No, ma’am.” Don’t look white women in the eye. Be silent. Be invisible.

Mose Wright, who was in Chicago for a funeral, accompanied Parker, his grandson, and Till, his great-nephew, on the train. When they arrived in Mississippi, they drove back to Wright’s home on Dark Fear Road, east of Money. His own youngest child, Simeon, was two years younger than Till. A few days later, the boys went to Bryant’s Grocery. That’s where Till whistled at Carolyn Bryant, a 21-year-old white woman the press described as beautiful.

Simeon and Parker were standing right there when he whistled. They both knew immediately that there would be trouble. Parker later told me that Till saw the fear in his cousins’ eyes and he got scared too. Till begged them not to tell Mose what he’d done. For the rest of his life, Simeon regretted not saying anything.

Till and Simeon shared a small bed while Parker slept in another room. A few nights later Simeon woke up to Mose standing over them with Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, who held his pistol in one hand and a flashlight in the other. Simeon’s mother begged the men not to take the boy, and offered what little money they had. The kidnappers became aggravated when Till, groggy and disoriented in the dark, insisted on putting his socks on. Simeon would never forget the look of fear on his cousin’s face.

Mose followed them outside. He heard what sounded like a woman’s voice saying they’d gotten the right kid, just before the men took Till and drove away. Mose stood outside staring down Dark Fear Road long after the dusty trail disappeared.

Simeon’s mother swore she wouldn’t sleep in that house another night, and she didn’t. She moved to her brother’s house that same day and from there went to Chicago, where she spent the rest of her life. A few days later, Simeon saw a sheriff’s deputy come to the field to find Mose. There was a whispered conversation he couldn’t hear and then he saw his father leave quietly. When Mose got home from identifying the body, he could only sit on the porch swing and grunt.

The old man agreed to testify, and when asked to identify J. W. Milam in court he pointed a finger and said in a booming voice, “There he is.” Some writers made him seem simple and country, quoting him as using the word thar, but Simeon said his father carefully enunciated the words: There. He. Is. After the trial, Mose joined his wife in Chicago and never returned to Dark Fear Road. Simeon came home to Mississippi for reunions but never lived in the Delta again. He wrote a book titled Simeon’s Story, in which he recounted that night and said he could never again hear the sound of an approaching car without thinking of 1955.

Not long before Simeon died, four years ago, he stood outside the abandoned and collapsing Bryant’s Grocery in Money with a group of Till scholars and activists. They headed to their cars. Next stop: the barn. One of them turned to Simeon, an old man by then, and asked if he wanted to come. He’d never been to the barn, not once in the 60 years that had passed since that night. Simeon shook his head.

“I’m not ready yet,” he said.

The barn’s history would have remained secret except for a single Mississippian. Early on the last morning of Emmett Till’s life, a Black 18-year-old named Willie Reed awoke and walked toward the town of Drew on the dirt road that still runs past the Andrews place.

Reed was heading to a nearby country store to get breakfast. He saw a green-and-white Chevrolet pickup truck turn onto the path that led up to the barn. Four white men sat shoulder to shoulder in the cab; in the back three Black men sat with a terrified Black child. The child was Emmett Till.

Reed heard Till screaming in the barn. At one point, he saw J. W. Milam take a break and walk with a gun on his hip to a nearby well. Milam drank some cool water, then went back inside and the beating continued. The screams turned to moans.

The men talked about taking Till to a hospital, but they’d beaten him too badly to be saved. So much about this murder remains unknown, but FBI investigators believe a single gunshot to the head ended Till’s life in the barn. The men threw cotton seeds on the floor to soak up the blood and took the body to the Tallahatchie River. They threw Till off a bridge; a cotton-gin fan tied to his neck pulled him down.

Willie Reed went to work the next day. By then word had spread, and people were starting to talk. His grandfather begged him to stay quiet and not create trouble for the family. Reed thought over and over about whether he should tell the truth about what he’d seen and heard.

Aretired fbi agent named Dale Killinger knows more about the murder of Emmett Till than anyone else alive. Killinger was the lead agent when the FBI opened a federal investigation in 2004, with the potential to finally bring charges against Carolyn Bryant for her presumed role in the murder.

I talked to Killinger on the phone one afternoon about the violence in the barn. The next time we spoke he told me that his wife had been sitting next to him during that graphic conversation, and when he’d hung up, she’d turned to him with a hollow look in her eyes and asked him why they’d done it. Even when people know generally what happened to Till, the specifics still leave them gasping.

“Rhea, don’t you understand?” he told her. “They were entertained by this.”

“What do you mean?” she said.

“They could’ve killed and tortured him anywhere they wanted to,” he told her. “They chose to take him to a barn where they could control the environment and do what they wanted. In my mind, they were entertaining themselves.”

He told me he’s imagined the sounds of that night over and over. He interviewed Leslie Milam’s widow before she died and found her evasive.

“Frances Milam was home,” he said. “She was in the house. You think she heard what was going on?”

Killinger laughed bitterly and answered his own question.“Hell yeah, she did,” he said. “It’s 1955 and you don’t have air-conditioning. So she admitted that they brought him to the farm in the middle of the night. That’s in the FBI report. So she was there and they were beating him and eventually somebody shot him in that barn in the head. You hear everything in Mississippi! You know? The windows are open. You have window screening—that’s all you have. You hear a car coming a mile away. You hear somebody getting beat in your barn! You hear a gunshot! Think about why they chose to go to that barn. They chose it because Leslie Milam controlled that space. And they could go in there and do what they wanted, how they wanted. And why would you do that? You could have taken him off in the woods and killed him if you wanted to, right? Dump the body anywhere. They went out of their way.”

The white mississippians who lived around the barn responded to the killing like an organism fighting an infection. A new narrative took hold, about how the community of good white people was unfairly tarnished by the actions of a few monsters. In 1955, the editorial page of the Chicago Defender, the preeminent Black newspaper in the country, chronicled this self-absolution as it happened. “Most of the educated upper class white Mississippians are desperately trying to disassociate themselves from the lynchers,” the paper said, “trying to show that they are civilized and do not approve of such racial violence.”

Three months after Till’s death, according to records in the Sunflower County courthouse, Leslie Milam’s landlord, Ben Sturdivant, sold the property and threw him off the land. Last summer, his grandson Walker Sturdivant showed me into his office on the family’s sprawling farm. All around were the telltale signs of old Delta money: a chair from a fancy boarding school, a Union Planters Bank espresso cup, photographs from ski vacations. Walker’s dad was a respected, progressive politician, and the family had recently helped the Emmett Till Interpretive Center acquire land for a memorial site on the Tallahatchie River.

Before we talked, Walker had gone down to the courthouse to pull up the old rental agreements and land records so he’d have his facts straight. It’s all there, in red leather-bound books. “Immediately after it happened,” he said, “that’s when he exited from his relationship. Dad always said J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant both had been ostracized in the white community after what they had done. The people just decided: At least the code said you don’t do that to children.”

During the trial, people put up jars in stores around the Delta to raise money for Bryant and Milam, but once the pair got paid for the magazine confession, they were essentially exiled. Bryant lost his store because almost all his customers had been Black and nobody would shop there anymore. He moved around a lot, broke and shunned. J. W. Milam lived out his final years in a Black neighborhood, the only place he could afford. He kept getting in trouble—for writing bad checks, for assault, for using a stolen credit card.

Leslie Milam lived better than his brothers but only marginally so. Nineteen years after the murder, his wife called their minister, a Baptist preacher from Cleveland, Mississippi, named Macklyn Hubbell. She asked him to come to their home, on the outskirts of town. Milam wanted a moment of his time, a meeting first reported in Devery S. Anderson’s book Emmett Till. Hubbell drove over to the house, and Frances led him into a room where Milam was stretched out on the couch. “I remember exactly,” Hubbell, 90 years old and sharp, told me. “I remember approaching the couch where he was lying.”

The preacher pulled up a straight-backed chair.

Milam looked him right in the eye and began to speak.

“It was a confession between Leslie and me,” Hubbell said. “And I didn’t share it with anybody until Leslie was gone and Frances was gone. Because they are gone, I can tell you what Leslie said. I remember that he said he was involved in the killing of Emmett Till. He wanted to tell me, because he perceived me to be a man of God. He was releasing himself of guilt. He was belching out guilt.”

Hubbell listened and prayed, and then he left the small ranch house on a street surrounded by farmland. Milam died before sunrise. He’s buried in Drew, a few miles from the barn where he helped torture and kill a child.

One of the things Dale Killinger did when the FBI opened its case was go looking for Willie Reed, the man who as an 18-year-old had heard Till screaming in the barn. Reed had ignored the warnings of his grandfather and agreed to testify. He said later he couldn’t have lived with himself if he’d stayed quiet.

After the trial, mobs searched the Delta for the witnesses. Reed knew he needed to escape. He walked and ran six miles from his home outside Drew. A car waited at a rendezvous spot and carried him to Memphis, where for the first time in his life he boarded an airplane. U.S. Congressman Charles Diggs of Detroit flew with him as an escort. When they landed in Chicago, all Reed had were the clothes on his back plus a coat and an extra pair of pants.

He tried to start a new life in Chicago but suffered a breakdown. Eventually, he changed his name to Willie Louis and got a job at Jackson Park Hospital, where he met a woman named Juliet. They married and bought a home in the Englewood neighborhood, on the South Side. They both worked at the hospital for decades, she as a nurse and he as an orderly.

Juliet didn’t know about her husband’s old name until they’d been together for at least a decade. Then, in the 1980s, a journalist tracked him down. An aunt had given the reporter his address. Quickly realizing that she shouldn’t have done that, the aunt called Juliet to let her know what was about to happen.

“Do you know who Willie is?” she asked.

“He’s Willie!” Juliet said.

“He’s the boy that testified in the Emmett Till trial.”

That’s how Juliet learned about her husband’s previous life. Willie was angry at his aunt but told the reporter everything. Juliet listened. After that, he’d talk about Till occasionally, but only if someone asked. “He was trying to forget,” she says.

Sometimes Juliet would catch Willie lost in silence.

“What’s wrong?” she’d ask.

“I was just thinking about Emmett,” he’d reply, then fall silent once more. He told her that he was reliving Till’s screams.

Two more decades passed, and then Killinger called. He said that the United States needed Willie Louis to go back to Mississippi. Back to the barn, so he could walk agents through his old testimony and be ready to give it again. Louis invited Killinger to the house in Englewood, and Killinger promised to be by his side every moment. Only then did he agree.

The FBI bought Willie and Juliet plane tickets and flew them down South, into the Memphis airport. The next morning, Willie looked out on newly planted cotton fields as the men from the FBI drove him deeper into the Delta. Killinger wondered what he must have been thinking. Until the day his grandfather died, the old man had told anyone who’d listen that Willie should have kept his mouth shut. Willie had built a new life in Chicago, a respected quiet life, but the feeling of exile had never quite gone away.

They drove mostly in silence. After two hours, they turned onto Drew Ruleville Road and parked. Willie Louis became Willie Reed again. He stood on the empty grass where he’d once lived. His house was long gone, and so was the country store where he’d been headed when he saw the truck.

Louis moved slowly up the road, across the bayou and the dentist’s manicured lawn.

“I could hear screaming,” he said.

“Which part of the barn?” Killinger asked.

“On the right side,” he said.

Then Willie Louis got to the barn itself. Killinger watched him closely as he walked into a past reaching out to grab him, back into a life he’d left behind. Everything felt new and strange. The old man stood with his arms out, like someone who’d lost his balance, and he tried to make sense of then and now on this terrible piece of dirt.

Willie louis died in 2013, and Simeon Wright died in 2017, leaving Wheeler Parker as the last surviving witness to the kidnapping. He’s working on a memoir. He wrote it in longhand and his wife, Marvel, typed it for him, at times weeping as she read things she hadn’t known, even after five decades of marriage.

Now a pastor, Parker met me this past spring in a Chicago suburb at a community center named for Till. It sits on a piece of land where he and Till used to play.

“Cowboys and Indians,” he said with a smile.

The community center is just feet from where his grandfather Mose Wright used to keep a vegetable garden after he testified in the trial. A painting of the store in Money hangs on the wall near portraits of Martin Luther King Jr. and Barack Obama.

That week in 1955 was the defining moment in Parker’s life. He remembers riding the train south from Chicago with Till. He remembers hearing Till whistle at Carolyn Bryant, and he remembers the night when J. W. Milam shined a flashlight in his face.

“They came to me,” he said. “I was shaking like a leaf. Whole bed was shaking. I closed my eyes and said, ‘This is it.’ And I was praying. I said, ‘God if you just let me live, I will be doing right,’ because I thought of every evil little thing I’ve done wrong, you know? Oh, man, I was begging.”

He looked at me, and there was silence. It was 1955 again for just a moment.

I asked him how many people are alive who grew up with him and Till.

He started counting.

“Well, around here,” he said, and the names started coming: first his own brothers, then a local shoeshine man who used to play war games with them right where we were sitting. He kept rattling them off: Joanne, Mary Ellen, Louise, Lee. Nine or 10, he finally told me. He paused.

“Ms. Bryant’s gonna be 87 this year,” Parker said. “She’s five years older than I am. I’m 82 last week.”

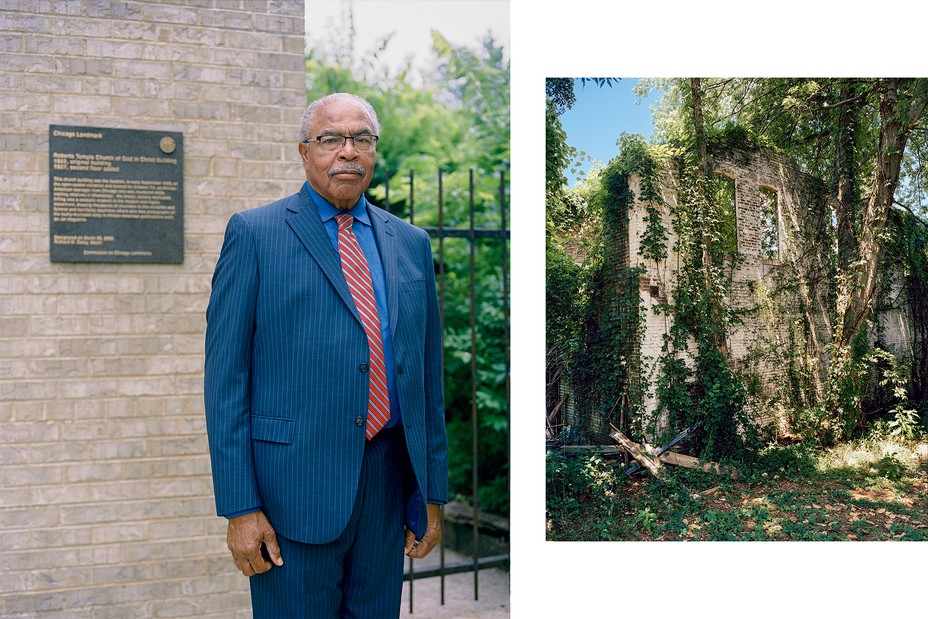

In the decades after the murder, the old Bryant’s Grocery in Money became a strange underground tourist attraction, a place that offered truths about America, or maybe just satisfied some morbid curiosity. The family of one of the jurors bought the store and then let it collapse. Now the building is falling in on itself, overgrown with vines, ivy, and trees. In the owners’ desire for the store not to become a monument to a killing, it’s become something else: a monument to the desire, and ultimate failure, of white Mississippi to erase the stain of Till’s death.

Meanwhile, the barn vanished from the popular account of the murder, and then it faded from all but a few local memories, too. The land around it just kept on being plowed and planted and harvested. A local farmer named Reg Shurden and his family moved into the farmhouse next to the barn in the late 1950s. They didn’t stay long. Shurden’s wife didn’t like it and never really explained why.

“When my grandmother was still living, I didn’t realize that’s where Emmett Till had been killed,” Stafford Shurden says. “Now I wonder, did she hate it because she knew that happened?”

In the early 1960s, a couple from Missouri, the Buchanans, moved onto the farm with their two children. Their son, Bob, was a junior in high school then. He says his father didn’t know the history of the land when he bought it. The barn was just where they stored seed and farm equipment. But one day he was in there helping out when someone pointed.

“That’s where they tied up Emmett Till,” the man told him.

Buchanan says he didn’t think about it much after that. His family never discussed it, even among themselves. They just went on with their lives.

In the early 1980s, Bob’s mother rented the land near the barn to Reg Shurden’s nephew Steve. “Miss Buchanan was a sassy old little lady when I knew her,” Steve says. “The house was getting run-down then. She kept talking about how she was going to fix it up.”

He knew about the barn.

“We didn’t think about it,” he says. “I mean, it wasn’t anything to talk about.”

His cousin Stafford sat with us at a Drew lunch spot as we talked.

“As a kid, I didn’t know who Emmett Till was,” he said.

Mrs. Buchanan refused to leave even as the house deteriorated around her. Finally, sometime before 1985, she moved out and the place sat abandoned. High-school kids started going out there to drink. They would sit in the dark front room, with the big bay windows looking out on the cypress trees and the bayou, and either they didn’t know Emmett Till had died there or they didn’t care. I bet they didn’t know. That innocence was what their parents and grandparents had wanted. Sometimes the kids would go through Mrs. Buchanan’s drawers and find old farm bills and letters and paperwork. It was like she’d up and vanished one day.

Jeff Andrews loved the view across the bayou, and after Mrs. Buchanan died he begged Bob and his sister to sell him the property. He pestered them for close to a year until they relented. He’d lived in Drew for most of his life. He didn’t know he’d bought the barn where Emmett Till was killed. Nobody told him.

Around the time of the sale, on a spring Saturday night, the house caught fire. Instead of paying to have the debris removed, Andrews got a bulldozer and a crew to dig a big hole and push the ruins of Leslie Milam’s old home into the hole and cover it up with Mississippi dirt. He built a new house, and finally his father told him about the barn. Andrews never asked his dad why he hadn’t mentioned it sooner.

Agroup of fbi agents once asked Wheeler Parker what justice looked like to him. That’s a hard question. His cousin Simeon always wanted to see Carolyn Bryant behind bars. Parker told the agents he just wanted people to know the truth.

Over the decades, evidence and facts had slowly vanished. The only copy of the trial transcript disappeared, and FBI agents had to track down a copy of a copy of a copy, which a source led them to at a private residence on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. The ring Till had been wearing, which had belonged to his father, vanished. In the 1970s, the Sumner courthouse was renovated and old evidence was discarded. A lawyer in Sumner looked on the curb of the courthouse and saw the gin fan that had been used to sink Till’s body sitting with all sorts of meaningless trash bound for the dump. He took it as a trophy but soon threw it away.

A recording of Roy Bryant’s account of that night in 1955 exists. The tapes are either in Mississippi or in Los Angeles, where the United American Costume Company is based. That’s the company founded by John Wayne’s personal costumer, a native of Ruleville, Mississippi, named Luster Bayless. Decades ago, Bayless decided he wanted to make a movie about the Till murder and so he arranged an interview with Bryant. A microcassette recorder captured every word as Bryant drove around the Delta, re-creating the night of the murder; it is likely the only existing description of what happened inside the barn in the final hour of Till’s life. Bryant even posed for a Polaroid in front of the store. Other than FBI agents and a few random people, nobody has heard the recording.

These tapes contain something other than facts, although they contain lots of those, too. They contain the sound of Bryant’s voice, the way his laugh sounds when he recounts torturing a child, the way he drawls his vowels, the little details that let you know a human being did this terrible thing. Locals remember Bryant as an old man, blinded by a lifetime of welding, working at a store on Highway 49 in Ruleville, eight miles from the barn.

The researcher Bayless hired, a woman named Cecelia Lusk, told me she went to the libraries at Delta State and Ole Miss and was stunned. Stories about Till had been torn out of magazines in the archives. In both of the courthouses in Tallahatchie County, she said, she found the legal file folders for the case. They were empty. “Not one sheet of paper,” she said. “Someone had removed everything. There was absolutely not one piece of paper in those folders.”

This is the world of silence Killinger entered when he started asking questions around the Delta, trying to find Wheeler Parker’s idea of justice and maybe Simeon’s too. He went to Carolyn Bryant’s home to question her; when she dies, that interview will become public. He tracked down missing transcripts and uncovered new evidence. A forensic team searched Andrews’s barn but came up empty.

A central pillar in the 1955 defense of Milam and Bryant had been that the body Mamie Till buried was not, in fact, her son’s—that it was instead a body planted by the NAACP. One juror later told a reporter that he’d voted to acquit because the body had chest hair and everyone knew that Black men couldn’t grow chest hair until they were about 30. Killinger knew prosecutors would have to deal with that accusation if they were to bring charges against Carolyn Bryant, and so he had to ask the Till family for permission to bring up the body and conduct a DNA test.

The family held a small service, and then the diggers went to work. They removed the concrete vault and then the casket. After the casket came out, the vault crumbled. Emmett Till had been buried in a glass-top coffin, and the glass hadn’t broken. The assembled people gasped, according to Killinger, who was there. The embalmer, Woodrow “Champ” Jackson, a Black man from Tutwiler, Mississippi, had clearly done his work with care. Emmett Till looked just as he did when they put him in the grave. The FBI photos taken in 2005 looked almost exactly like the famous Jet pictures that helped spark the civil-rights movement.

Killinger presented his report and waited; he thought there was enough evidence for an indictment. But nothing happened. A local prosecutor tried—not hard enough, in Killinger’s opinion—to indict Carolyn Bryant for manslaughter, but a grand jury declined. That was 14 years ago. A reporter heard the news and found Simeon Wright at his local church. He said he knew he didn’t have many years left and now he knew he’d die without seeing Carolyn Bryant spend a minute behind bars. The members of the grand jury looked in the mirror, he said, and didn’t like what they saw.

Icalled jeff andrews a month or two after my first visit to the barn and asked if I could come back and talk. I explained that I felt compelled to do this story because one of the central conflicts for white Mississippians is whether to shine a bright light on the past or—

“—move on?” he said, finishing my thought.

That remains a fraught and divisive question for white Mississippians. Should you dig deep enough that you might come to hate a place you also love? When Andrews graduated from dental school, he and his wife visited a town in Alabama where a practice was for sale. They both liked the area and thought they could make a great living—and a great new life—there. But they both felt out of place. “It’s a long way from home,” Jeff’s wife said.

They moved back to Drew and have never left. Last year, Andrews went duck hunting 40 of 65 possible days. He drives a tractor in the early morning and late afternoon, working his soybean fields and listening to sports talk radio. He never got rich, but he’s built the kind of life he dreamed about. Andrews talks about the love he feels for the land around his home—not just the piece he owns, but all of it, a kind of spiritual homeland. His family arrived here by way of a New Deal program two generations ago. He still farms the original 40 acres that his grandfather farmed, about a mile from the barn.

Andrews and I talked on and off in the months that followed our first meeting. He seemed genuinely at ease. He told me it didn’t bother him to own the barn, or sleep near it, or grill while kids splashed in the pool in its shadow. I couldn’t understand how the knowledge of what had happened there wasn’t grinding away somewhere deep inside him. How a place that was the literal site of the torture and execution of a 14-year-old boy could be a place of such peace for him.

Finally, at his suggestion, I got in touch with a woman who’d written a book about her experiences communicating with the spirit of Emmett Till. She asked whether I’d talked to the Andrews family about the noises and lights. I said I had not. They’ve seen and felt things, she told me. A flash. A rush of movement. They’ve heard noises. The woman said Andrews’s wife talks to Till sometimes.

I asked Andrews about this, and he hemmed and hawed but eventually told me that his daughter believes Till’s spirit is on their land, that their home is haunted by the memory of the boy who died there. Let that idea sit for a moment: If ghosts aren’t real, which they’re not, and if these apparitions are the only way for deeply buried feelings to find the light of day, then the gap between what the Andrewses allow themselves to know and what they keep buried inside is the exact gap that memorials are designed to bridge. And so Jeff Andrews has a choice.

Money is being raised to buy the barn and turn it into a memorial, with the idea that it might one day become part of the national park Wheeler and Marvel Parker hope to create. The Parkers want the centerpiece of that project to be the Chicago church where Till’s funeral was held and where the world saw his open casket. That is the story of Mamie Till’s courage and strength, whereas the barn is a symbol of white violence and fear. The barn remains a mirror.

Andrews knows an offer is likely coming for his land and home, and he isn’t sure what he’s going to do.

Fourteen years ago, Tallahatchie County issued a formal apology for the acquittal of Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam. The state installed a green historical marker outside the courthouse. Patrick Weems’s office is across the street from that sign, so he can literally point out his window at progress. But he can also point to the repeated vandalism of signs his organization has worked to erect. There was a marker at the Delta Inn, the hotel where jurors were sequestered and where, during the trial, a cross was burned just in case any of the jurors didn’t understand what their neighbors expected of them. That marker was taken down one night by vandals and has not been replaced. A sign was placed along the Tallahatchie River, where Till’s body was found, but someone threw it in the water. A replacement collected more than 100 bullet holes until, made illegible by the violence, it came down and was given to the Smithsonian. A third sign got shot a month after it went up. Three Ole Miss students posed before the sign with guns, and one posted the photo to Instagram. The current sign is bulletproof.

Little about this murder feels safely in the past. Wheeler Parker is alive. So is Carolyn Bryant. Many of the children and grandchildren of the killers and the jurors and the defense attorneys still live in the area. The barn is still just a barn. One man claims that the truck used to kidnap Till is rusting right now on a Glendora plantation. Two of the four men suspected of being in the cab of that truck back in 1955 went unnamed in public until Killinger’s FBI report was released. Till’s ring remains missing, and the legal files remain missing.

But J. W. Milam’s gun, which Willie Reed saw strapped to his hip and Wheeler Parker saw when the flashlight hit his face, isn’t one of the many pieces of this story that vanished without a trace. The FBI suspects that it didn’t vanish at all. When I first heard that the gun might still be in the Delta, I didn’t believe it. Then I got a local crop-duster pilot on the phone. Yes, he confirmed, he and his sister believe they own J. W. Milam’s military-issue pistol, as well as the holster. The siblings don’t really know what to do with the gun. Maybe, the pilot said, they could get local celebrity Morgan Freeman to buy it from them and donate it to a museum. The pilot explained that their father had gotten the gun from one of Milam’s attorneys, and upon their father’s death it passed down to them. Right now, he said, that gun is locked away in a safety-deposit box in a bank in Greenwood, Mississippi. It’s a model 1911-A1 .45-caliber semiautomatic, made by Ithaca, serial number 2102279. The gun still fires.

This spring, wheeler Parker drove me around Argo, Illinois, southwest of Chicago, showing me the places where he grew up. He told me more about the group of old men who went to elementary school with Till all those decades ago. They were planning to gather on what would have been Till’s 80th birthday for a weekend celebration. Parker said the old guys sit around and tell stories about the place where they were born.

“Oh,” he said, “Mississippi is talked about all the time.”

He laughed.

“Behind the iron curtain,” he said.

He pulled over in front of an empty lot with houses on both sides. This little industrial suburb is where Emmett Till lived before he and Mamie moved to the South Side. The kids used to play across all these yards. An old fire hydrant is out front, and Parker looked at it closely. It’s the original. The fire hydrant remains but the home is long gone.

“Emmett Till’s house is right here,” he said, pointing to the empty grass. “And 7524, our house, was right next door here.”

They rode bikes together on this street. They told jokes and made plans. Till wanted to do whatever his older cousin Parker was doing. That’s why he asked his mom to let him go to Mississippi. Because Parker was going down to visit his grandparents. Till begged. Mamie said no at first but finally relented. Parker had to face Mamie when he got back to Chicago from the Delta. He still remembers how guilty he felt in her presence for surviving, and he will forever carry that guilt, and also the resolve it put in him.

He and Marvel are raising money for the memorials, to make sure that when they die, and the others who knew Emmett Till die, Till’s story will be remembered. They will continue telling his story for as long as they’re able. Because Till rode his bike on this street. Because the gun still fires, because the barn is still just a barn, because time is thin and fragile, because the dirt Jeff Andrews and I were taught to love is the exact same dirt Wheeler Parker was taught to fear.

–theatlantic.com