In the four decades before the Civil War, an estimated several thousand enslaved people escaped from the south-central United States to Mexico. Some received help—from free Black people, ship captains, Mexicans, Germans, preachers, mail riders, and, according to one Texan paper, other “lurking scoundrels.” Most, though, escaped to Mexico by their own ingenuity. They acquired forged travel passes. They disguised themselves as white men, fashioning wigs from horsehair and pitch. They stole horses, firearms, skiffs, dirk knives, fur hats, and, in one instance, twelve gold watches and a diamond breast pin. And then they disappeared.

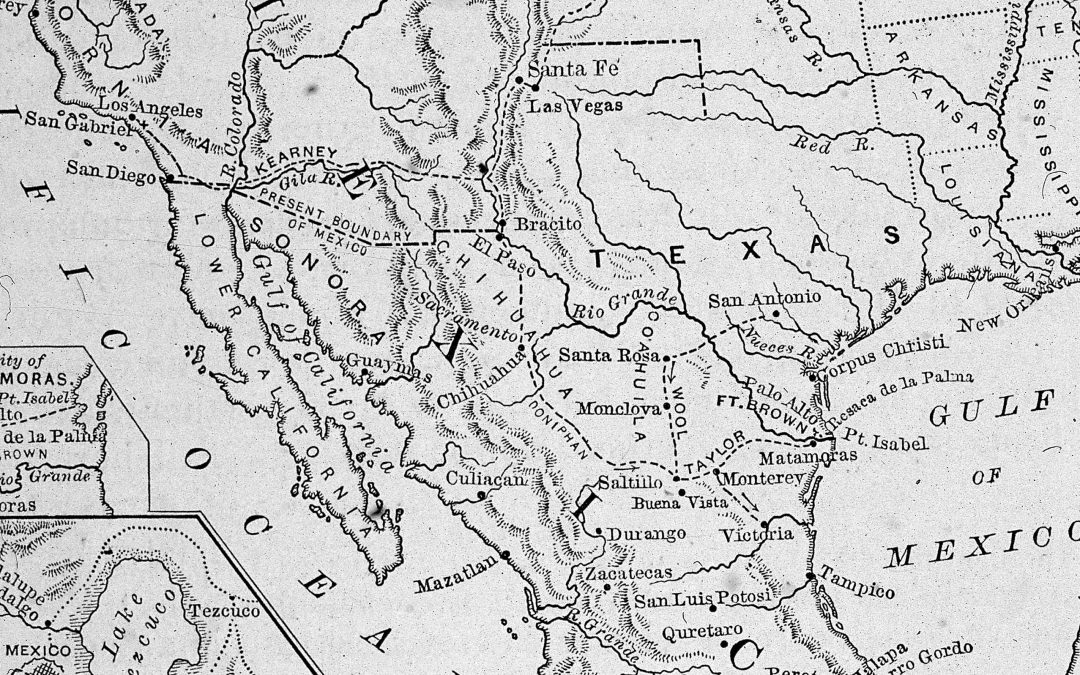

Why did runaways head toward Mexico? For enslaved people in Texas or Louisiana, the northern states were hundreds of miles away. Even if they did manage to cross the Mason-Dixon line, they were not legally free. In fact, the fugitive-slave clause of the U.S. Constitution and the laws meant to enforce it sought to return runaways to their owners. Mexico, by contrast, granted enslaved people legal protections that they did not enjoy in the northern United States. Mexico’s Congress abolished slavery in 1837. Twenty years later, the country adopted a constitution that granted freedom to all enslaved people who set foot on Mexican soil, signalling that freedom was not some abstract ideal but a general and inviolable principle, the law of the land.

Two options awaited most runaways in Mexico. The first was to join Mexico’s military colonies, a series of outposts along the northern frontier, which defended against Native peoples and foreign invaders. The second was to seek employment as servants, tailors, cooks, carpenters, bricklayers, or day laborers, among other occupations. Their lives were by no means easy, and slaveholders pointed to these difficulties to suggest that bondage in the United States was preferable to “freedom” in Mexico. Noah Smithwick, a gunsmith in Texas, recalled that a slave named Moses had grown tired of living off “husks” in Mexico and returned to his owner’s “lenient rule” near Houston. Another came back from his “Mexican tour” in 1852, according to the Clarksville, Texas, Northern Standard, with a “supreme disgust” for Mexicans. The conditions in Mexico were so bad, according to newspapers in the United States, that runaways returned to their homes of their own accord.

Some enslaved people did return to the United States, but typically not for the reasons that slaveholders claimed. In 1858, a slave named Albert, who had escaped to Mexico nearly two years earlier, returned to the cotton plantation of his owner, “a Mr. Gordon of Texas.” The Independent Press in Abbeville, South Carolina, reported that, “like all others” who escaped to Mexico, “he has a poor opinion of the country and laws.” Albert did not give Mr. Gordon any reason to doubt this conclusion. He remained at his owner’s plantation, near Matagorda, Texas, where the Brazos River emptied into the Gulf. But Albert did not come back to stay. Five or six months after his return, he was gone—this time with his brothers, Henry and Isaac. What drew them across the Rio Grande gives us a crucial view of how Mexico, a country suffering from poverty, corruption, and political upheaval, deepened the debate about slavery in the decades before the Civil War.

Northern Mexico was poor and sparsely populated in the nineteenth century. During the winter months, Comanches and Lipan Apaches crossed the Rio Grande to rustle livestock, and the Mexican military lacked even the most basic supplies to stop them. Local militiamen did not have enough saddles. Military commanders asked “the coöperation of the female population” to provide their men with uniforms. Town councils pleaded for more gunpowder. Desperate to restore order, Mexico’s government issued a decree on July 19, 1848, which established and set out rules for a line of forts on the southern bank of the Rio Grande. A previous decree provided that foreigners who joined these colonies would receive land and become “citizens of the Republic upon their arrival.”

In 1850, several hundred Seminoles moved from the United States to a military colony in the northeastern Mexican state of Coahuila. Eighty-four of the three hundred and fifty-one immigrants were Black—formerly enslaved people, known as the Mascogos or Black Seminoles, who had escaped to join the Seminole Indians, first in the tribe’s Florida homelands, and later in Indian Territory. Fugitive slaves were already escaping to Mexico by the time the Seminoles arrived. In 1849, a judge in Guerrero, Coahuila, reported that David Thomas “save[d] his family from slavery” by escaping with his daughter and three grandchildren to Mexico. A year later, seventeen people of color appeared in Monclova, Coahuila, asking to join the Seminoles and their Black allies. Another two men, José and Sambo, claimed to be “straight from Africa,” according to one account. By 1851, three hundred and fifty-six Black people lived at this military colony—more than four times the number who had arrived with the Seminoles the previous year.

Life in Mexico was not easy. Few fugitive slaves spoke Spanish. (“Couldn’t even ask for a chaw of terbacker!” a son of a Black Seminole remembered in an interview with the historian Kenneth Wiggins Porter, in 1942.) Most had so little taste for Mexican food that they scraped the red beans from the tortillas their neighbors handed them. But the Mexican government did what it could to help them settle at the military colony, thirty miles from the U.S. border. A priest arrived from nearby Santa Rosa to baptize them. A schoolteacher followed, along with crates of tools. With the help of the three hundred and seventy pesos a month that the government funnelled to the colony, the new inhabitants set to work growing corn, raising stock, and building wood-frame houses around a square where they kept their animals at night.

In this small, concentrated community, Black Seminoles and fugitive slaves managed to maintain and develop their own traditions. At the urging of the priest in Santa Rosa, they fasted every Friday and baptized the faithful in the Sabinas River. But when they kept vigil over the dead there was traditional stamping and singing around the bier, and when they took sick they ministered to one another using old folk methods. The demands of military service constrained their autonomy—fathers, husbands, and sons had to take up arms at a moment’s notice—but this also earned them the respect of the Mexican authorities. In 1851, a high-ranking official of Mexico’s military colonies reported that the “faithful” Black Seminoles never abandoned the “desire to succeed in punishing the enemy.” Another official expected that their service would be of “great benefit” to the country. The victories that they helped score against the Comanches and Lipan Apaches proved to Mexican military commanders that the Seminoles and their Black allies were “worthy of every confidence.”

For all of its restrictions, military service also helped fugitive slaves defend themselves from those who wished to return them to slavery. On September 20, 1851, Sheriff John Crawford, of Bexar County, Texas, rode two hundred miles from San Antonio to the Mexican military colony. There, he arrested two men he suspected of being runaways and carried them across the Rio Grande. José Antonio de Arredondo, a justice of the peace in Guerrero, Coahuila, insisted that the two men were both “under the protection of our laws & government and considered as Mexican citizens.” When U.S. officials explained that a court in San Antonio had ordered their arrest, the sub-inspector of Mexico’s Eastern Military Colonies demanded that they be released. Meanwhile, a force of Black and Seminole people attempted to cross the Rio Grande and free the prisoners by force.

Though military service helped insure the freedom of former slaves, that freedom came at a cost: risk to one’s life, in the heat of battle, and participation in Mexico’s brutal campaign against Native peoples. Not every runaway joined the colonies. Some settled in cities like Matamoros, which had a growing Black population of merchants and carpenters, bricklayers and manual laborers, hailing from Haiti, the British Caribbean, and the United States. Others hired themselves out to local landowners, who were in constant need of extra hands. Evaristo Madero, a businessman who carted goods from Saltillo, Mexico, to San Antonio, Texas, hired two Black domestic servants. Espiridion Gomez employed several others on his ranch near San Fernando.

These runaways encountered a different set of challenges. Those who worked on haciendas and in households were often the only people of African descent on the payroll, leaving them no choice but to assimilate into their new communities. Most learned Spanish, and many changed their names. (A former slave named Dan called himself “Dionisio de Echavaria.”) Fugitive slaves also encountered labor practices that bore some of the hallmarks of chattel slavery. In northern Mexico, hacienda owners enjoyed the right to physically punish their employees, meting out corporal discipline as harsh as any on plantations in the United States. In parts of southern Mexico, such as Yucatán and Chiapas, debt peonage tied laborers to plantations as effectively as violence. In 1849, a Veracruz newspaper reported that indentured servants suffered a state of dependence worse than slavery. In 1857, El Monitor Republicano, in Mexico City, complained that laborers had earned their “liberty in name only.”

But, in contrast to the southern United States, where enslaved people knew no other law besides the whim of their owners, laborers in Mexico enjoyed a number of legal protections. These workers could file suit when their employers lowered their wages or added unreasonable charges to their accounts. They could also sue in cases of mistreatment, as Juan Castillo of Galeana, Nuevo León, did, in 1860, after his employer hit him, whipped him, and ran him over with his horse. (His employer admitted to an “excess of anger.”) In general, laborers had the right to seek new employment for any reason—a right denied to enslaved people in the United States. And, more often than not, the greatest concern of former slaves who joined Mexico’s labor force was not their new employers so much as their former masters.

On August 20, 1850, Manuel Luis del Fierro stepped outside his house in Reynosa, Tamaulipas, a town just across the border from McAllen, Texas. The night was hot, and a band was playing in the plaza. As he stood listening, two foreigners approached, asking if he wanted to join them at the concert. Del Fierro politely refused their invitation. He did not give the incident much thought until later that night, when he woke to the sound of a woman screaming. Del Fierro hurried toward the commotion. In one of the rooms of the house, he came upon the two foreigners, one waving a pistol at his maid, Matilde Hennes, who “had been held as a slave in the United States.”

Hennes had belonged to a planter named William Cheney, who owned a plantation near Cheneyville, Louisiana, a town a hundred and fifty miles northwest of New Orleans. When Solomon Northup, a free Black man who was kidnapped from the North and sold into slavery, arrived at a plantation in a neighboring parish, he heard that several slaves had been hanged in the area for planning “a crusade to Mexico.” As Northup recalled in his memoir, “Twelve Years a Slave,” the plot was “a subject of general and unfailing interest in every slave hut on the bayou.” From her years working on Cheney’s plantation, Hennes must have known that Mexico’s laws would give her a claim to freedom. At some point—when or how is unclear—Hennes acted on that knowledge, escaping from Cheneyville, making her way to Reynosa, and finding work in Manuel Luis del Fierro’s household.

To del Fierro, Matilde Hennes was not just a runaway. As a servant, she was a member of his household. In the room, del Fierro took hold of his firearms, while his wife called for help from the balcony. One of the kidnappers, who was arrested, turned out to be Hennes’s former owner, William Cheney. In Mexico, Cheney found that he could not treat people of African descent with impunity, as slaveholders often did in the United States. While Cheney sat in prison, Judge Justo Treviño, of the District of Northern Tamaulipas, began an investigation into the attempted kidnapping.

Del Fierro’s actions were not unusual. In 1851, the townspeople of a small village in northern Coahuila took up arms “in the service of humanity,” according to a Mexican military commander, to stop a slave catcher named Warren Adams from kidnapping “an entire family of negroes.” Later that year, the Mexican Army posted a “respectable” force and two field-artillery pieces on the Rio Grande to stop a group of two hundred Americans from crossing the river, likely to seize fugitive slaves. In 1852, four townspeople from Guerrero, Coahuila, chased after a slaveholder from the United States who had kidnapped a Black man from their colony. They found the slaveholder, who pulled out a six-shooter, but one of the townspeople drew faster, killing the man. Unable to bring the kidnapper to court, the councilmen brought his corpse to a judge in Guerrero, who certified that he was, in fact, dead, “for not having responded when spoken to, and other cadaverous signs.”

The protection that Mexican citizens provided was significant, because the national authorities in Mexico City did not have the resources to enforce many of the country’s most basic policies. Mexico’s antislavery laws might have been a dead letter, if not for the ordinary people, of all races, who risked their lives to protect fugitive slaves.

Mexico has often served as a foil to the United States. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the population of the United States doubled and then doubled again; its territory expanded by the same proportion, as its leaders purchased, conquered, and expropriated lands to the west and south. Mexico, meanwhile, was so unstable that the country went through forty-nine Presidencies between 1824 and 1857, and so poor that cakes of soap sometimes took the place of coins. And yet enslaved people left the United States for Mexico. Although their labor drove the economic growth of the United States, they did not benefit from the wealth that they generated, nor could they participate in the political system that governed their lives. The United States Constitution acknowledged the right to property and provided for the return of “fugitives from labor.” The Mexican constitution, by contrast, abolished slavery and promised to free all enslaved people who set foot on its soil.

These laws had serious implications for slavery in the United States. Mexico bordered the American South—and specifically the Deep South, where slave-based agriculture was booming. Eventually, enslaved people escaped to Mexico with such frequency that Texas seemed to have much in common with the states that bordered the Mason-Dixon line. Samuel Houston, then the governor of Texas, made the stakes clear on the eve of the Civil War. “Texas is a border state,” he wrote in 1860. “Mexico renders insecure her entire western boundary. Her slaves are liable to escape but no fugitive slave law is pledged for their recovery.”

In fact, Mexico’s laws rendered slavery insecure not just in Texas and Louisiana but in the very heart of the Union. The land seized from Mexico at the close of the Mexican-American War, in 1848, was free territory. That territory included most of what is modern-day California, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. When Southern politicians attempted to establish slavery in that region, they ignited a sectional controversy that would lead to the overturning of the Missouri Compromise, the outbreak of violence in Kansas, and the birth of a new political coalition, the Republican Party, whose success in the election of 1860 led the southern states to secede from the Union.

It is easy to discount Mexico’s antislavery stance, given how former slaves continued to face coercion there. But these laws were a momentous achievement nonetheless. Only by abolishing human bondage was it possible to extend the debate over the full meaning of universal freedom. The enslaved people who escaped from the United States and the Mexican citizens who protected them insured that the promise of freedom in Mexico was significant, even if it was incomplete. As the poet Walt Whitman put it, “It is provided in the essence of things, that from any fruition of success, no matter what, shall come forth something to make a greater struggle necessary.” Their work—our work—is not over.

This essay was drawn from “South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War,” which is out in November, from Basic Books.

–newyorker.com