More than a decade ago, on the first day of a college seminar titled “The American South,” Glenda Gilmore—one of the deans of Southern history—challenged my classmates and me to define the borders of the South. It was a surprisingly difficult task. Everyone agreed on, say, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina, but what about Oklahoma—was it Western or Southern? What about Kentucky, home state of Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln? Perhaps Missouri, the setting of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn? Undoubtedly northern Florida, but whither Miami? Why not New Mexico, which after all is south of Virginia? Does Delaware count? The exercise ended without any certainty, which surely was the point.

To the eminent (and eminently racist) Southern historian U.B. Phillips, the South was defined by its weather. Elsewhere, he labeled white supremacy the region’s “central theme.” To others, the South is simply the former Confederacy. To many, there’s an unspoken but firm association between Southernness and backwardness, or religion, or poverty. These assumptions position the South as a region apart, an “other” place, an American heart of darkness, a foil for the more enlightened North or the more entrepreneurial West.

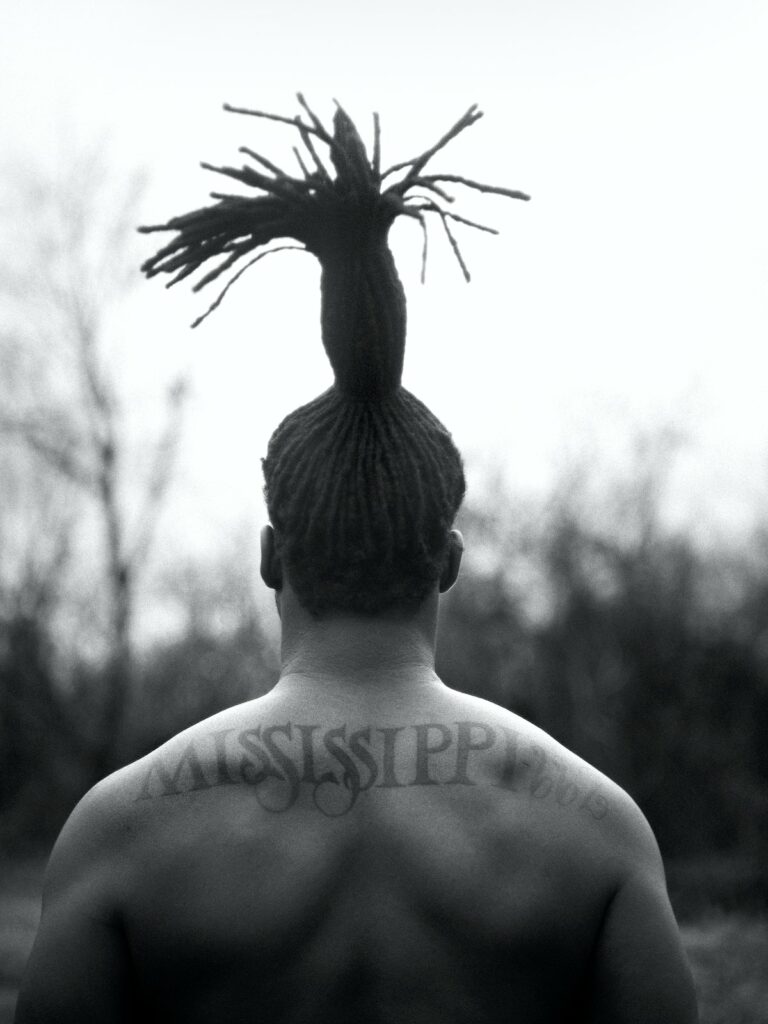

It’s ironic, then, that the South has also become a stand-in for American authenticity. “The most violent and inequitable region of the country produced a disproportionate amount of the modernist literature, adventurous self-taught art, and genres of music and popular styles of religion, which entered into and then transformed the artistic sensibilities and cultural soundtracks of the twentieth century,” writes Paul Harvey in a penetrating essay in A New History of the American South. Consider the iconic American musical forms, the blues, jazz, country, gospel, soul—all have Southern origins. What would American religion look like without Southern Baptists, Pentecostals, the broader evangelical movement? Is modern American literature even imaginable without William Faulkner, Zora Neale Hurston, Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, or Thomas Wolfe?

Edited by the acclaimed University of North Carolina historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage, the 15 essays in A New History recount the origins, histories, and influences of the South. The specter of “Southern distinctiveness”—the idea that the region is uniquely, characteristically violent or dysfunctional—hangs over the collection, but it “is not an organizing conceit in this volume,” Brundage writes. Instead, he and his contributors have attempted something rarer: an entirely new narrative of the American South. Again and again, its essays emphasize that the South has not been static, “steeped in timeless traditions,” but rather has been “punctuated again and again by wrenching transformations.”

A dynamic South. The idea is counterintuitive precisely because of the prevalence of magnolia-shrouded imagery, because of accounts that position the South as the consistent spoiler, emphasis on the consistent. But the South that emerges from A New History is fresh and exciting in its unfamiliarity.

It is a region of unstable boundaries, demographics, and politics, a site of shifting powers and protean culture. The South hasn’t always been a place of cruelly concentrated wealth, of rigid racial boundaries, of grinning, sweating, sloganeering, archconservative politicians. It has also been a launchpad of change, of radicalism, of resistance—and its future is yet unwritten.

In the beginning, there were monsters. To stroll through the Ice Age South would be to encounter many familiar plants—from maples and hickories to, yes, magnolia and dogwood—but also giant land tortoises, giant moose, giant beavers, dire wolves, American lions, and (in Florida) giant armadillos.

The coastlines were well over 100 miles beyond where they are today, and only with the warming of the globe did the glaciers retreat, the rivers stabilize, and the Southern forests assume a now-familiar ecology. Most of the great American megafauna died off.

Humans occupied what is now the South for many thousands of years—most Southern Native American origin stories involve west-to-east migrations, a narrative supported by the archaeological record—but the end of the Ice Age about 11,000 years ago spurred the development of larger communities, the centralization of political power, increased trade, increased warfare, and eventually the domestication of plants and a transition to agricultural societies. Thus did climatic change set in motion the first of the South’s series of metamorphoses.

In A New History’s first essay, the historical anthropologist Robbie Ethridge covers these millennia of transformations swiftly yet with aplomb and respect. Eventually, the colonizers arrived. First came the Spanish, who encountered a dense web of chiefdoms and a century of resistance. Even as other imperial powers—the English, the French—set up small outposts, Native Americans continued to constitute the majority of the region’s population until well into the eighteenth century.

The Revolutionary War had been monstrously costly, a destructive cataclysm, and an economic downturn and widespread anger followed in its wake. This spurred a rise in Southern “localism”—a desire for greater control over local affairs—yet “the South” was not yet perceived as (nor did its residents perceive themselves as belonging to) a distinctive region. It was, among other factors, fights over slavery that hardened the categories of “the North” and “the South.”

The Southern states were home to an agricultural political economy deeply dependent on slavery, and even as abolition took hold in Haiti, Spanish-controlled Latin America, and (parts of) the British Empire, powerful Southerners united in support of the system that enabled the mass cultivation of rice, tobacco, and cotton. Dissenters (of many races) fled north or west; ideas of whiteness solidified in the aftermath of Indian expulsion and the expansion of suffrage to poorer white men; slave-state politicians began to identify as “Southerners”; and, as Martha S. Jones writes in her essay, Northern abolitionists began speaking of slavery as “a distinctly southern problem.”

Of course, the South remained a site of “porous” boundaries, as Kate Masur emphasizes in her chapter. It was home to a diverse array of immigrants, defiant Native communities, and vibrant (and surprisingly mobile) slave subcultures. Rail and steam transport, as well as the global commodities trade, connected the South to the world at large, and the region’s southern border shifted as settlers in Texas warred with Mexico over land.

The diversity of crops, climates, and types of social organization meant that each area had its own distinctive political orientation, a fact that frustrated those, like Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who pushed for a collective Southern separatism.

Eventually, those in power—“planter-politicians,” to borrow a term from Gregory P. Downs’s essay—grew so fearful of abolition that they launched a war. “By drawing a sharp political line around the Confederate states,” Downs continues, “the war made real what had only been metaphorical.” From a distance of a century and a half, it’s easy to forget that the South could have won the war.

“There was in fact nothing foreordained about the survival of the American nation,” Masur writes, noting the proliferation of new nations and revolutionary movements throughout the nineteenth century. Only through a combination of enhanced industrial capacity, the neutrality of European powers, and Black rebellion so widespread that W.E.B. Du Bois would label it a “General Strike” did the North clinch victory and keep the South as merely the southerly region of a larger nation.

Over time, the English—with Native allies and Native slaves and then, increasingly, African slaves—became more powerful, spreading from Virginia to Maryland to Carolina (not yet bifurcated), but social relations remained malleable. Some seventeenth-century Africans lived freely in the South; some even owned slaves themselves; and others worked for a time as indentured servants, a status they shared with legions of poor and striving whites.

In the mid–seventeenth century, fearful that the growing class of temporary and former servants might displace them, white property owners passed laws that phased out indentures for white people and established a system of chattel slavery (permanent and heritable) for Black people. This effectively divided the working class along racial lines, exactly as the tobacco planters and colonial overlords intended. Indeed, many historians have shown how this transformation created the modern idea of race itself. The English colonies transformed, Jon F. Sensbach writes in his essay, “from a society with slaves to a slave society.”

Slavery grew to such an extent that some areas (famously South Carolina) became majority Black in the eighteenth century, and plantations began farming rice, drawing on captured Africans’ knowledge of the crop. Slave revolts became common features of life in the South, and many Black people escaped and found refuge in the declining Spanish colony of Florida or within Native communities.

“It may be no exaggeration to say that in the southern colonies, enslaved Africans made the first bids for independence, helping to trigger the Revolution,” writes Michael A. McDonnell in his essay. Escape attempts and rumors of impending armed revolt greatly heightened tensions within the Southern colonies, with many colonists believing that “the British would liberate slaves.” When revolution eventually broke out in the mid-1770s, many in the South were either loyal to the British or too focused on the “threat of insurrection by enslaved Africans” to join the war effort. The Continental Congress made George Washington of Virginia the head of its army in an attempt to gin up Southern support for the war, but thousands of “loyalists” across the region nonetheless waged guerrilla warfare against the revolutionaries. In the end, the British were simply too disorganized to exploit their advantages (including the legions of Black people fleeing to their lines), but victory in the war for colonial independence was “a close-run thing,” McDonnell concludes.