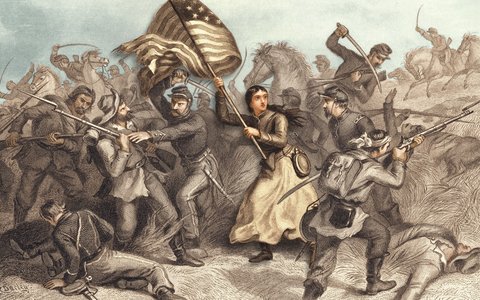

Statues of men in uniform, Union and Confederate, astride their big horses, still dot the landscape of the North and the South: Brave men, no doubt, but where were the women during those bloody years? Consider not just what women suffered during the Civil War—bad enough—but what they did. Recall the famous ones, like the intrepid nurse Clara Barton, and the lesser known but just as determined, like Arabella Barlow, who darted so often through the Virginia countryside to scare up supplies that her Union comrades dubbed her “the Raider.” After the Battle of Antietam, when she located her husband, Francis, a colonel in the Army, languishing in a military hospital, she nursed him back to health, and at Gettysburg, learning that he’d been critically wounded again—and left for dead—she presumably crossed Confederate lines to find him. In 1864, though, while working at the City Point Hospital, she contracted what appeared to be the typhus that killed her.

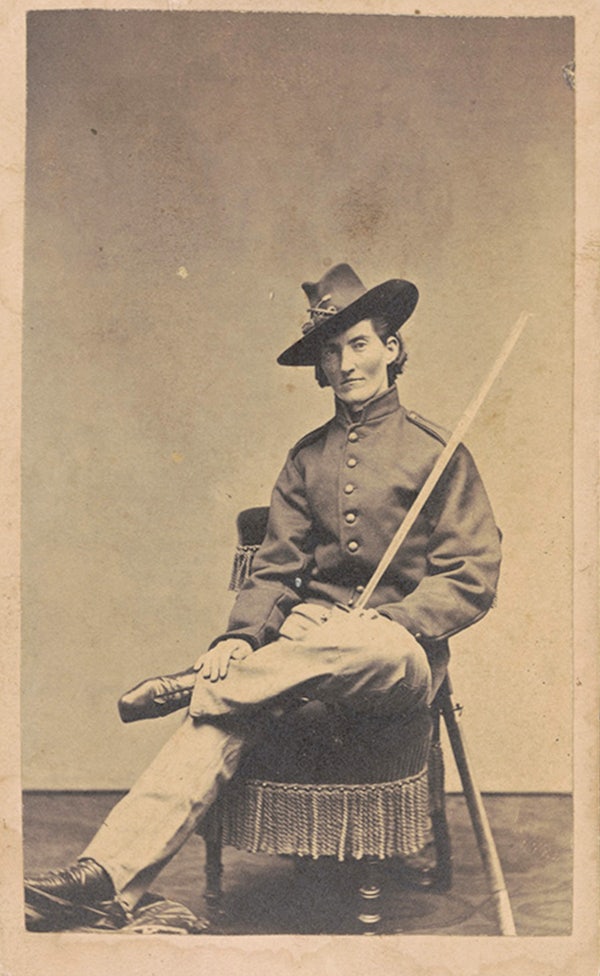

Not surprising: Nurses routinely died during the war. Hannah Ropes, head nurse at the Union Hotel Hospital in Washington, succumbed to typhoid pneumonia, and Louisa May Alcott, who had worked by her side, was similarly infected, though luckier. Alcott’s father traveled all the way to Washington from Massachusetts to fetch her, because when female nurses fell ill, Alcott later said, the doctors disappeared. But women did more than succor the sick and wounded. Sarah Edmonds was a nurse, yes, but also a soldier, who participated in the First Battle of Bull Run and in the Peninsula Campaign; one general later wrote, “her sex was not suspected by me or anyone else in the regiment.” Edmonds was also a spy. Not surprising, either; so were a number of women. Take Mary Bowser, the freed slave in Jefferson Davis’s home who, with her photographic memory, recited the details of various government documents to Union officers nearby and recounted for them the conversations she’d overheard at the Davis dinner table.

Of course, such spies as Rose Greenhow were more notorious. A prominent Washington hostess before the war, she headed an espionage ring in the capital once the fighting started; she warned General Beauregard before Bull Run of Union General McDowell’s intentions, which helped in no small measure to ensure a Confederate victory. Imprisoned for a year, in the spring of 1862 she was deported to Richmond, where Jefferson Davis soon packed her off to England and France in order to raise money for the Confederacy. On her way home, the blockade runner she traveled on ran aground; she then convinced several men to row her to shore near Wilmington, North Carolina, but she drowned; the boat capsized, and it was said the gold sovereigns she was carrying back to Davis had weighed her down.

Then there were the women, enslaved and free, who offered covert or open resistance in the form of guerrilla warfare. Mary Surratt ran the boardinghouse where John Wilkes Booth met with the other Lincoln assassination conspirators. Accused of being one of them, she was the first woman ever to be executed by the federal government, a dubious honor. When asked about clemency, President Andrew Johnson said that there hadn’t been enough women hanged in this war.

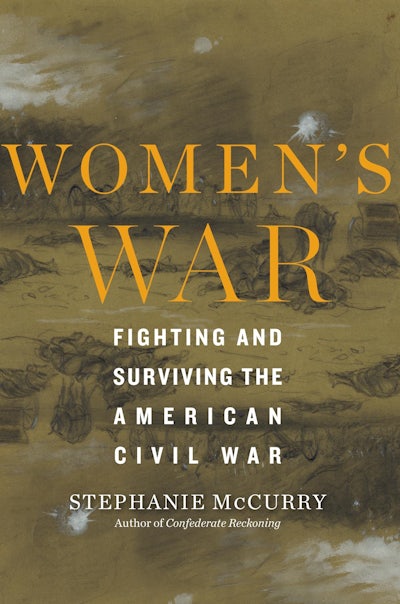

Yet the myth of women as innocent bystanders persists, partly because women generally don’t tell war stories, as McCurry observes, and because of historians’ approach to women and war. Women who participate in war are “disowned—or rendered exceptional.” McCurry wryly quotes, for example, the military historian John Keegan, who writes that war “is the one human activity from which women, with the most insignificant exceptions, have always and everywhere stood apart.” McCurry emphasizes that such misguided, partial history not only ignores women as active participants, indirect participants, and even perpetrators of war but also fails to comprehend how women in war, as she awkwardly writes, “pose challenges of governance that shape the history of war as profoundly as men in uniform and armies of the field.” What she means, it seems—and as her book amply illustrates—is that during wartime, the ways women choose or are forced to survive often compel governments to reconsider and actually change their policies.

How did women get written out of Civil War history? At the time, their participation was recognized at least to some extent, and laws were rewritten to make that clear. In the summer of 1862, the Union commander, Major General Henry Halleck, asked his friend Francis Lieber, a law professor and political theorist at Columbia College, to help define “military offenses” of “treasonable character,” because up to that point so many activities—burning bridges, cutting telegraph lines, spying—did not necessarily fall under the definition of treason and in any case could be tried only where the act had occurred. Lieber complied, though at first he still assumed that enemy women were to be considered outside the theater of war. But just months after he issued his guidelines, a frustrated General Halleck was forced to acknowledge that guerrilla fighters could be women as well as men; again, ignore them at your peril. Halleck issued orders: Any rebellious civilian, regardless of gender, “not only forfeits all claim to protection, but subjects himself or herself to be punished either as a spy or military traitor.”

Rebel women were subsequently arrested, tried, sentenced, and remanded to prison. And, as McCurry then suggestively writes, the treatment of women as combatants marked a turning point in the war. The distinction between the private individual, or civilian, and the soldier was erased. General William Tecumseh Sherman announced, “we are not only fighting hostile armies but a hostile people,” and waged war on them in turn. Backed by his superiors, Sherman forced the evacuation of the entire civilian population of Atlanta, including women and children; he said he was uninterested in “the humanities of the case.” Waging war on women might seem barbaric, he admitted, but he had the law on his side.

After the war, however, Lieber rushed to restore gender hierarchies, making sure power rested overwhelmingly with men. (“How would we like a woman president?” Lieber scoffed in response to demands for women’s suffrage.) Lieber was propping up the conventional view of the family by insisting that the only parts women had played in the war were as wives, mothers, or daughters. And so he was essentially bolstering “the heterosexual, patriarchal family”—and, according to McCurry, the state.

In the second of her three chapters, McCurry turns her attention to the status of black women. Early in the war, when three fugitive male slaves showed up at the Union stronghold Fortress Monroe, Virginia, the commanding general, Benjamin Butler, effectively emancipated them by declaring them “contraband” of war. He put these men to work digging entrenchments, even though at the time there was no legal basis on which the Union general could free them. Still, he successfully argued that by holding these men, he was depriving the Confederates of the use of their labor; his argument became de facto government policy. But, as Butler worried, if he took the men who now began rushing to the fort, wasn’t he obliged morally to take the women and children? Sure, he was depriving the rebels of their workforce, but was there a legal argument for holding, protecting, or freeing women and children? It’s a crucial, intriguing question. The way the Union Army saw it, the black woman was neither a laborer nor a soldier; she was a burden.

The question became even more critical as the war progressed. At least 500,000 refugees, probably more, flocked into Union lines throughout the areas under federal occupation. The situation rapidly developed into a humanitarian crisis, with many a Union commander worrying about what to do with thousands of people they termed “useless negroes.” And specifically what to do with all the homeless females and children rushing into the Union lines for protection?

To deal with the crisis, according to McCurry, the military reinvented the family as a moral and practical necessity, conferring on refugee women the “privileged identity” of wife; this had been Butler’s solution at Fortress Monroe, where the Reverend Lockwood, a relief agent, began to officiate at the marriages of former slaves (who had been deprived of the right to marry under slavery). An unmarried black woman refugee might easily be branded a vagrant or a prostitute. “Marriage, monogamy, and the Christian family were official Union policy,” McCurry notes. As a consequence, the formerly enslaved woman was relegated to a position of dependency, either on her husband or on the state; her very freedom “was unimaginable without marriage,” McCurry declares. From that point of view, these women were handed over from one master to another. It was a jury-rigged solution, undergirded by a paternalistic ideology. (Yet later in her book, McCurry does praise “the formation of free black families” as “the most successful part of the entire reconstruction process.”)

Though the status and fate of the formerly enslaved black woman are crucial to any study of the Civil War, it’s an area routinely ignored even by many recent historians. There are, however, a number of stories about the fate of the plantation mistress, the subject, more or less, of McCurry’s final chapter. She recounts the postwar hardships endured by a Georgia woman named Gertrude Thomas. Born a member of the slaveholding planter class, Thomas swiftly descended into poverty after the war. Crops were failing and land prices falling. Her husband neglected to find or adequately pay for labor, sank deeper into debt, and was soon sued by several local banks as well as grocers and merchants. All the while, she held tightly to her twisted view of privilege and of the presumed fealty her former slaves owed her.

To McCurry, who swerves away from what she calls meta-history here, the saga of Gertrude Thomas represents “a gendered history of defeat.” For Thomas’s response to her miserable situation was grief, outrage, and a preoccupation with the bodies of black women. Tacitly, Thomas begins to acknowledge that the men in her life had ceaselessly betrayed her, having sexually violated black women to father many of their children. But this leads her to decide that black women were immoral and simultaneously fear that interracial marriage might become acceptable. To this, add her confidence in white supremacy, the better to reassert, or maintain, white power in the face of a new, racially diverse social order. Thomas shared her husband’s hatred of Reconstruction, and she largely endorsed such terrorist tactics as violence and murder to prevent black men and white Republicans from going to the polls.

At the same time, she understood why black men wanted to vote. Denied political rights herself, Thomas appreciated the importance of the vote: “If the women of the North once secured to me the right to vote whilst it might be ‘an honor thrust upon me,’” she confided to her diary, “I should think twice before I voted to have it taken from me.” And thus as she grew older, she became a suffragist and a liberal (to a degree) as well as an old-timey Confederate.

Thomas’s late-life crusades on behalf of voting rights for white women as well as public education for all may be representative—or not. For as McCurry unequivocally reminds us, we need to know much more about the role of white Southern women, whether in maintaining white supremacy or in the fight for justice right after the Civil War. Without learning more about the lives of all these women, black and white, during the war and after, we cannot fathom history, macro or micro. Make no mistake, women are never outside of history; they act and change and suffer and subvert. Their presence isn’t odd. What’s odd is that we’ve failed to see them so long. Time has come, then, not just to remove statues but to place women atop some warhorse, where for better or worse they’ve always been.