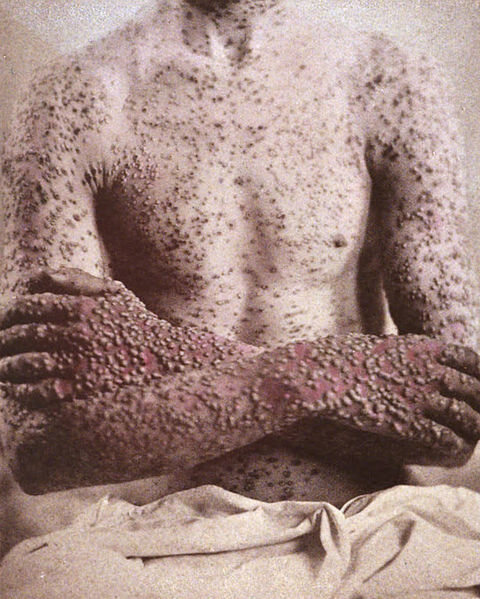

Bullets fly, the cold creeps in, and your body is so malnourished that you can barely walk. You know that if smallpox gets a hold of you, you don’t stand a chance. You look at your fellow soldier’s pus-filled lesion and realize there is only one way to survive the smallpox outbreak in your unit. You breathe in deeply, cut your arm open with your rusty pocket knife, and fill the wound with the liquid coming out of your comrade’s pustule.

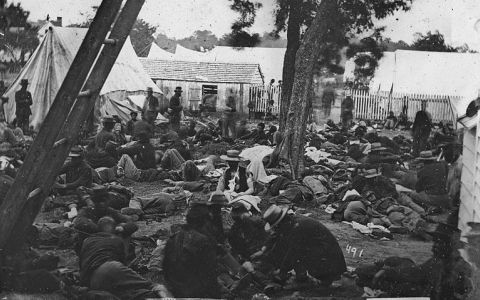

Strange as it may sound, this was the reality for many Union and Confederate soldiers of the American Civil War. In the 1860s, before germ theory had taken hold in the field of medicine, medical facilities often lacked the necessary hygiene to prevent infections. Because of this, thousands of soldiers were killed by simple infections and diseases we now consider non-threatening or obsolete. Of these, smallpox was perhaps the deadliest and most feared.

Plaguing the world since ancient times, smallpox brought down powerful rulers like Pharaoh Ramses V, and has been credited with aiding the fall of Rome and the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. It also led us to discover vaccination.

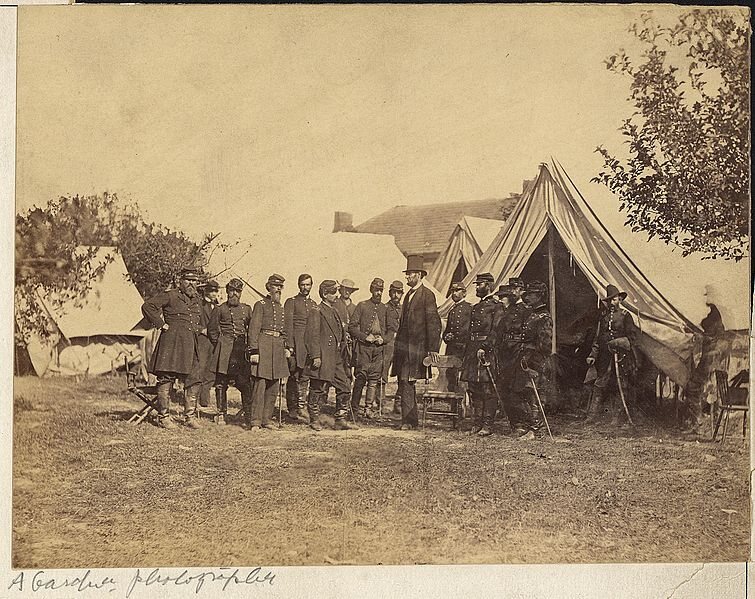

By 1861, the year in which the Civil War broke out, the western world had been vaccinating against smallpox for over half a century. This feat is accredited to Edward Jenner, an English scientist who demonstrated that infecting people with the less threatening cowpox disease would result in immunity to smallpox. Injections were yet to come, so doctors’ preferred vaccination method was to gather fluid from an active pustule of an infected cow or person and introduce it into the patient’s bloodstream by making a cut in the skin. While prone to certain complications, this method proved effective enough to be exported from Europe to the rest of the world.

During the American Civil War, vaccination was not easily achieved—though it was highly desirable. It was difficult to either find a cow or a suitable person with an active pustule that could be harvested to vaccinate others. Smallpox outbreaks were common on both sides, as were resulting deaths. According to the The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine by Glenna R Schroeder-Lein, the most accepted method was to look for small children to infect with cowpox. Once infected, doctors would wait seven or eight days for a pustule to fully form, puncture it, and take the lymph (fluid) from it. Alternatively, they would wait for a scab to form and then take it out.

Depending on whether it was the lymph or the scab, the virus could stay active from a couple of days to two or three weeks. Doctors would deep cut or scrape off the skin of new patients and introduce the lymph or scab directly into their bloodstream. After the virus took hold, the lesions from the newly vaccinated could be used to infect more children and more soldiers, in a never-ending cycle of purposefully transmitting festering body fluids from one person to the next.

But why would doctors specifically target children to help infect soldiers with cowpox? The simple answer lies in one of humanity’s least favorite topics: venereal diseases. Doctors knew that these diseases were common among soldiers, and that there was a risk of transmitting them through this method of vaccination. There was also the fact that smallpox and cowpox lesions look very similar to syphilis lesions, and can be easily confused. Children, then, provided the perfect solution to the risk.

Perhaps in peace time this would have worked, but not in the middle of a war. Joseph Jones, a southern scientist who after the war attempted to recover medical data, calculated that there was one doctor for every 324 soldiers in the south and one for every 133 soldiers in the north. Add to this appalling numerical disparity the shortage of medical supplies, the lack of sanitary conditions, and the high number of wounded soldiers, and you can see how extensive vaccination was almost impossible.

If you were a soldier out on the field, threatened by a smallpox outbreak, practicing arm-to-arm vaccination on yourself often seemed like the best, if not only, solution. After all, this informal method of vaccination seemed like a smaller risk than the ones they faced daily.

How would soldiers with no medical experience achieve this process? As Margaret Humphreys graphically describes in Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War, with the doctor too busy or completely absent, soldiers resorted to performing vaccination with whatever they had at hand. Using pocket knives, clothespins, and even rusty nails (again, most people had no concept of germs yet), they would cut themselves to make a deep wound, usually in the arm. They would then puncture their fellow soldier’s pustule and coat their wound with the overflowing lymph. Afterwards they could do nothing but hope for the best.

The best, however, was not very common in this scenario, as it too often led to spurious vaccination, or an attempt at vaccination whose result was unsuccessful or harmful. As common sense in the 21st century dictates, self-inflicted wounds made with unsterilized materials led to infections. While in some cases, the pain ended at that, it sometimes led to serious complications that would cause a need for amputation, and in extreme cases, death.

As if that wasn’t enough, there was also the problem of the commonality of venereal diseases. In the transmission of lymph into the bloodstream, soldiers would often get infected by their fellow soldier’s diseases, particularly syphilis. As you recall, there is an unfortunate similarity between smallpox and syphilis. This meant that some soldiers, untrained in medical matters, could easily confuse a syphilis pustule with a cowpox one. Thinking they could be immune to the terrifying smallpox, many Civil War soldiers accidentally infected themselves with syphilis.

Certainly, most cases of syphilis contracted during the war were, so to say, orthodox. Sex workers were common in stations and occupied cities, and the last worry on a soldier’s mind in that moment were venereal diseases. There were those unlucky enough, however, to contract the horribly painful disease through a self-inflicted wound rather than carnal pleasure.

If we are intent in finding a lesson to this story, let it be this: Even in the most dire circumstances, don’t cut your own arm and fill the wound with your friend’s infected bodily fluids. The results may surprise you.